Psyche in the Operating Theatre by David Holt

Contents

Introduction

1 Transference Solicitation

2 Reminding, Showdoing, Letting Be

3 Enactment, Therapy, Behaviour

4 The Public Organisation of Psychotherapy - medicine, law, religion, education, aesthetics

5 Psychoanalysis and Religion

6 Government – letter from the Secretary of State

– an Explanation

– notes for meeting at the Department of Health

Introduction

These papers, written over the last ten years, were all inspired, or provoked, by the debate that has been going on about the regulation of psychotherapy. I have collected them together like this so as to define my own position, and perhaps to suggest to others certain long term considerations.

The order in which they are presented is not chronological. The first, Transference Solicitation, was completed last. Although it originates in notes first written down in October 1993, it has been revised many times since. It developed immediately out of teaching work in supervision, and indirectly out of my interest in published and anecdotal reports of the work of the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy, the British Association for Counselling, and the British Confederation of Psychotherapists.

The other papers are all referred to in the first, and therefore amplify and help explain its argument.

Reminding, Showdoing, Letting Be, was written in 1989, and published in Harvest, the Journal of the C G Jung Analytical Psychology Club London, with a response by Renos Papadopoulos. In this I wrote:

“Thinking about how I would like to see psychotherapy organised and taught I have come to identify three movements or modalities. I think of these as movements of the mind and heart and intellect which are both spiritual and technical. I call them the re-minding, the letting be, and the showdoing. I believe that psychotherapy should be so organised and taught as to allow for the fullest possible exchange between these three modalities.”

After ten years, and I think in particular of experience I have shared with others at the Oxford Psychotherapy Society, I remain convinced that this is what we should be working towards.

Enactment, Therapy, and Behaviour, was written as a chapter in the book Dramatherapy: Theory & Practice 2, edited by Sue Jennings and published by Routledge in 1992. It places my interest in “showdoing” in the context of theatre, in work that I began when I wrote my thesis at the Jung Institute in Zurich in 1965-6, and which continued from the mid 1970’s in association with the Sesame tradition, and in the interdisciplinary weekends at Hawkwood College in Gloucestershire.

The Public Organisation of Psychotherapy was written for an informal monthly group meeting in Oxford, and published subsequently in the Bulletin of the Oxford Psychotherapy Society, and the Newsletter of the Westminster Pastoral Foundation’s Institute of Psychotherapy and Counselling. In it I tried to look at our problems of organisation and definition from the point of view of Government.

Psychoanalysis and Religion was written for the Oxford Pastoral Counselling Service in November 1994.

Finally, I include three examples of personal exchange with Government. The first is a letter from the Secretary of State for Health to my Member of Parliament, dated 5th May, 1993, replying to my enquiry as to how I stood professionally. The second is the Explanation which I then wrote at her suggestion. The third are notes which formed the basis of a meeting at the Department of Health on 25th September, 1995.

I have left the layout of the various diagrams uneven so as to emphasise how tentative they are.

1 Transference Solicitation

These notes were first written in October 1993, and revised in November 1994, March and October 1996, May 1997, and July 1998. They developed immediately out of teaching work in supervision, and indirectly out of my interest in the movement towards public regulation of psychotherapy and counselling.

Some background on this is necessary to put transference solicitation in context.

In July 1993 I had written a short ‘Explanation’ of my professional standing, in response to a letter of the Secretary of State for Health of 5 May 1993. In that ‘Explanation’ I had asked

i) that religious experience, both as avowal and critique, should have more influence in the organisation of psychotherapy;

ii) that we develop a unified view of psychotherapy and counselling;

iii) that we air doubts about psychoanalysis and its influence;

iv) that clients, patients and their families be given more of a say.

I also referred to a much longer paper of mine, published in 1988. In that paper I had written:

“Thinking about how I would like to see psychotherapy organised and taught I have come to identify three movements or modalities. I think of these as movements of the mind and heart and intellect which are both spiritual and technical. I call them the re-minding, the letting be, and the showdoing. I believe that psychotherapy should be so organised and taught as to allow for the fullest possible exchange between these three modalities.”

Subsequently I had taken this ‘Explanation’ further, and at a meeting at the Department of Health in September 1995 had presented a short paper arguing that proper regulation of psychotherapy and counselling must involve the public. What was needed was a participatory, rather than a protective, culture.

In these notes I try to relate that argument to professional interest in transference. Regulation must take account of the fact that our profession solicits transference. We need a culture in which those who are solicited can find their voice and register their vote.

Solicitation

I work in and with and through transference and countertransference. But I see both as grounded in what I call ‘transference solicitation’.

Much of our professional talk about transference seems to assume that what happens is that the patient begins it all by projecting on to the therapist, and that the therapist responds by counter projections onto the patient But this is not how it goes. It is the therapist who begins it all, by putting herself forward in a way that solicits projections. She puts up a brass plate. He gets himself listed somewhere. She takes a job with a socially recognised label attached to it He has himself included on a grape vine of friends and colleagues through which all kinds of projections are already flowing.

Transference/countertransference doesn’t begin with the patient The patient comes into a situation which is already pulsing with transference solicitation, which already has channels of expectation to act as conductors. The studies of transference and countertransference in the textbooks and journals presuppose this matrix of solicitation. They don’t scrutinise it.

As psychotherapy and counselling try to establish themselves as accountable professions there is pressing need for such scrutiny. I think the public rightly suspect of us of being up to something which we do not altogether own. In soliciting transference it is easy to presume more than is admitted.

These notes attempt an account of my own experience of solicitation. What I have to say is organised round four diagrams.

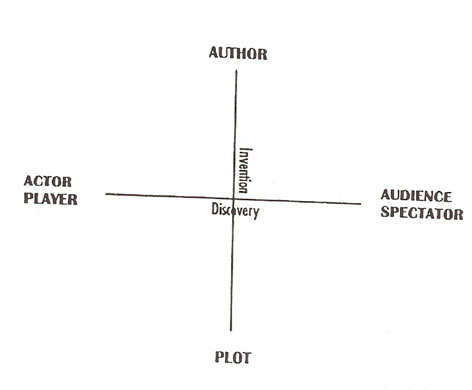

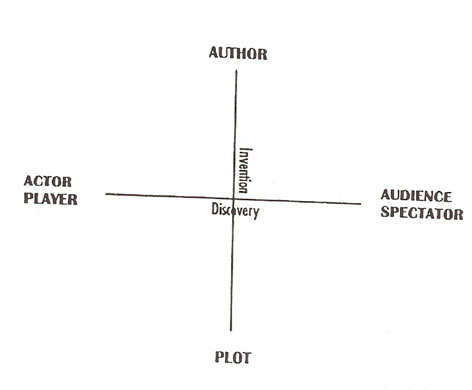

First diagram: transference and theatre

My first version of this (known to colleagues and students as ‘the dramatic model’) was drawn out in the early 1970’s, when I had been practising for seven or eight years. It approaches transference through drama and theatre, and allows us to reflect on how making, knowing, and doing are related.

Working with transference can involve verbal interpretation. It can also involve performance, demonstration, and what l think of as ‘letting be’, all of which are interpretive.

Interpretation is about meaning. Meaning can be discovered. It can also be invented. So whether it be verbal, performative, demonstrative, or letting be, interpretation partakes of both discovery and invention. We have to allow for both.

I have described in published papers how my attitude to transference and counter transference has been influenced by theatre. It was at the theatre that I realised that projection (of which transference is one example) is grounded in a field of solicitation. I have tried to draw out the field in this dramatic model. (I discuss the evolution of this model over twenty years of practice in the paper included here on Enactment, Therapy, Behaviour.)

This allows for an understanding of interpretation as solicited by two kinds of making, discovery and invention, and indicates how it is possible to operate with both while maintaining the distinction between them.

Note for instance how it opens up a field which:

(1) recognises inventiveness (author) as existing in its own right, not as something that is learned from experience

(2) allows for both text (the vertical axis between author and plot) and performance (the horizontal axis between actor and audience), making it clear that neither can be reduced to the other, so that

(3) performance calls for interpretation in terms of text, and text in terms of performance.

It seems to me that in much of our talk about transference there is an emphasis on the lower and right hand triangles of this model at the expense of the upper and left hand. The Author as maker is suspect. It is as if we believe that inventiveness is nothing more than a kind of discovery. Doing is subordinated to knowing. Interpretation apart from action is preferred, as apparently more detached, more clinical, more objective.

Psychoanalysis in particular seems to be grounded in suspicion of the Author ‘position’.

There is something taboo about the arc between Actor and Author. Its theory of the unconscious collapses Author into Actor and Audience, thus authorising symbolic systems testable only by those who have themselves submitted to the test. The body is kept still. Movement (‘acting out’) is suspect. What I have called the modalities of letting be and showdoing are radically devalued. Actor’s access to Author, and Author’s need for Actor, are collapsed into transference interpretation. Psychoanalysis thrives on teachings and trainings which foster such collapse.

And it does not exist in a vacuum. In soliciting transference its practitioners profit from, and contribute to, wider cultural collapse of Author into Actor and Audience. (See George Steiner’s book length discussion of the question “is there anything in what we say?” in his Real Presences, Faber 1989.)

My work owes much to psychoanalytic suspicion of the Author. It influences my approach to story and dream and symptom. I value the way it allows access to the body’s imagining of itself. But I cannot accept it as defining a profession.

On the contrary, it seems to me that it revokes the very idea of a closed profession. To be suspicious of Author is not just a state of mind. It is to take up a position. It is an act, a worldly act. It situates us in the world and it is constitutive of the world. In soliciting transference we assume some responsibility for that act.

We need the help of those right outside the psychoanalytic tradition. Psychoanalysis contributes to, and is fed by, a wider cultural, historical, theological, ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ (to use the term Paul Ricoeur gave us thirty years ago in his study of Freud), or ‘charisma of uncertainty’ (to use Stephen Logan’s term in his essay on “Challenges to psychotherapy in the postmodem age” in The Times literary Supplement of September 27, 1996). Public discussion of what we are up to in soliciting transference has to take into account this wider cultural investment in suspicion of Author.

So I have redrawn the dramatic model to open theatre into world.

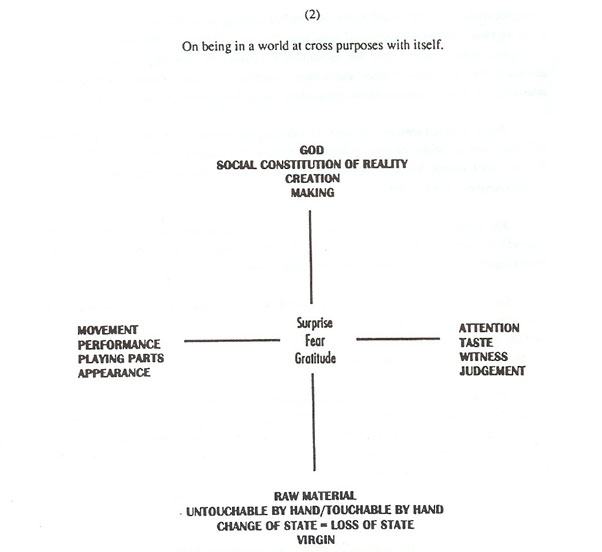

Second diagram: transference and the make up of the world

We live, contrarily, in a contrary world. (I pronounce the ‘a’ long, as in ‘Mary, Mary, quite contrary, How does your garden grow?’). It is a world in many ways at cross purposes with itself. There are lines of force and intention and desire which need to interact, to exchange, to ‘be crossed’ as in the breeding of plants and animals. But they also cross each other, contradicting, thwarting, frustrating, perhaps even double crossing themselves.

How is this contrary world made up? How do we participate in the making? How are our suspicions of that making brought into play and put to work?

I believe that transference solicitation is made possible by a shared investment in questions like that Our profession draws on public investment in the make up of a contrary world. What are our credentials for doing so?

This is what we are being asked to give an account of. Much has been written on the need for the individual to be creative. But if we are claiming a competence in making sense of the contrariness of both world and person then surely we have to allow questions about creation to arise and to be argued which go beyond individual creativeness. This second diagram is an attempt to show how this can be done.

Fundamental here is the idea of projection as a making, as one way in which we participate in an act of creation. Creation is projective. Transference solicitation arises out of our investment in that project. It assumes that there are connections between the make up, the creation, of the world and whatever it is that invites interpretation, and that ‘we have an interest in’ those connections. This assumption underwrites our work.

In drawing these axes at right angles to each other I am trying to picture a field in which these assumptions can be brought into the open and then tested. The words placed at the four points of the diagram are to remind us that this bringing out into the open and testing is not just a matter of psychology. It is a worldly act. It concerns our being in a made up world.

To emphasise this point, consider religion and law.

As regards religion: if we are to be suspicious of Author and yet also to be able to trust that things do make sense we need to allow for the difficulties of making and being made, for the difference between maker and made. It is irresponsible to solicit transference unless we are reflecting on and researching this difference. What is it like to participate in an act of creation, to be both maker and made? How are they different? How do we incorporate the difference? Howdo we account for it? Whatever else transference is about, it must include some response to that question.

Surely such response must refer to the presence or absence of God. We may not believe in God, but we must talk of God. We must air religious conviction, refusal, doubt, terror, confusion. Otherwise our suspicion of Author remains untestable.

It is a matter of feeling. In our work questions arise about the difference between maker and made which evoke feelings of trust and betrayal, hope and despair, purpose and intention, which are religious. If we don’t call them that their proper force is deflected: We cannot get our suspicion of Author into play between us without talk of God.

I know that bringing God into the conversation is socially embarrassing. But we need that embarrassment. If our regulatory bodies try to avoid it they will not engage with the pervasive cultural influence of suspicion of Author and our public will not be helped to find their own voice with which to challenge our presumptions.

So this second diagram is designed to open questions present in the dramatic model into God questions. They are questions like: why does Author need the play between Actor and Audience to realise Plot? Do Actor and Audience have to take account of Author’s intention? What if Author cannot recognise its creation in the Plot as realised between Actor and Audience? How is Plot affected if Author loses interest in its creation?

These are questions about the making of meaning. “I had the meaning once, but it has gone missing”. “I know there must be a meaning, but I can’t find it”. “I know what it means, even if nobody else does”. “There never was a meaning: I’ve been conned (or, you have conned me)”. (Was it G K Chesterton who said: “I’ve seen the truth, and it doesn’t make sense”?) Or simply, terribly simply: “there is no meaning”.

We meet all these in our work. The meeting can be appalling, tantalising, delusional, banal. What can we make of such confusion, such expectation, such disappointment? I don’t believe it is possible to do justice to the feelings at stake when we meet each other in the making of meaning without talk of God.

As with religion, so with law: how do we test our suspicion of Author in the domain of law? Laws are made, laws are kept, laws are broken. We are both free and bound to move between the three. It is because we are involved in their making that keeping law and breaking law don’t cancel each other out. Between the keeping and the breaking we test the powers and limitations of the making. This is what some of us refer to as the political process. Or, if we are more anthropologically inclined, as the social construction of reality.

We are both free and bound to move between making, keeping, breaking law. Our work as psychotherapists and counsellors is constantly manoeuvring round this dilemma. To get close to what is at stake here, for society as well as for individual, we have to recognise that law involves feeling that is religious. Like it or not, transference solicitation involves us in the politics of religion. Listen to talk about ‘ethics’ in our profession. Isn’t there something overdetermined in the tone of our voices, as if the word is loaded with an excess of meaning? I suspect that in talking about ethics we are often referring, shyly, evasively, nervously, to what an older tradition has called ‘practising the presence of God’.

The three words at the centre of the diagram are intended to help us talk about such practice. They are chosen to focus reflection on our personal awareness of, and response to, creation, to what it is like to be, ourselves made up, in a made up world.

We begin with surprise (wonder might be a better word), surprise which can astonish us so much that we cry out, tremble, perhaps even fall to the ground. Then there is our response to such surprise. I see this as having two faces: of fear, and of gratitude. To research the difference between maker and made we have to own to a mix of fear and gratitude in the face of our being in this world.

I draw the two axes at right angles to each other in order to allow for religious questioning of the difference between maker and made. I am trying to picture a field of behaviour and argument in which this difference can be owned. But remember: my diagram explains nothing. It suggests a field within which public enquiry into psychotherapy and counselling can include the politics of religion instead of bracketing it out.

To clarify connections between religion and law we can talk of cognitive affect, or affective cognition, as it arises between maker and made. Affect and cognition of this kind presuppose a special surprise. To incorporate them in experience we have to own that creation, the sheer givenness of personality and world, surprises us in a particular way, in a way that leaves us, willy-nilly, suspicious.

This is where we need to allow the other two words at the centre of the diagram to develop their full force. Fear and Gratitude. Gratitude and Fear. If we are really to bring our suspicion of Author into play, to put it to work, we have to allow that our surprise at creation leaves us in, puts us into, a state of both fear and gratitude.

We can illustrate this with reference to the words towards the bottom of the diagram. If we place ourselves in the position of ‘raw material’ (perhaps it ought to be spelt out more fully as ‘the made up out of’) what is creation like? What the maker understands as creation, the made up out of can experience as loss, waste, spoiling, abuse. Between maker and the made there has to be room for fear as well as for gratitude, for resistance that is both raw and virgin. If our public is to judge the work we do, and if we are to own up to what we do in soliciting transference, we need a meeting place in which ‘the made up out of’ can find its voice in the presence of the maker. My third diagram is an attempt to picture such a meeting place.

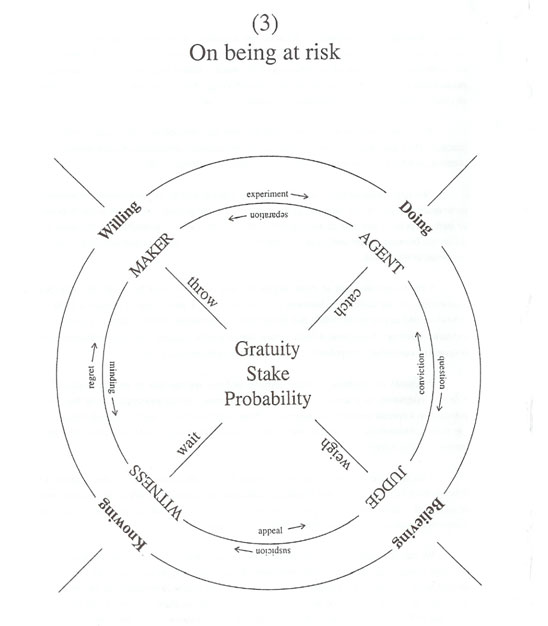

Third diagram: transference and risk

a) In introducing this I want to refer to the paper on the Public Organisation of Psychotherapy, in which I argue that our practice covers five areas of experience usually thought of as distinct from each other: medicine, law, religion, education, aesthetics. My third diagram is an attempt to place transference solicitation in a context that includes all those five words.

b) I have realigned the axes to suggest the possibility of rotation through a field. Maker and Judge, Agent and Witness, are set opposite each other to make room for the risk of creation. We are trying to bring judgment to bear on making. This allows us to be suspicious of Author, while keeping our suspicions themselves under scrutiny. We are not conflating Maker and Judge (as psychologies of the unconscious can so easily do). This opposition is necessary if we are to bring risk into our field of cross examination, and allow ‘the made up out of’ to find its voice over against the presumption of the maker.

Maker must be exposed to the risk of judgment, Judge to the risk of invention, so that we are both free and bound to move between the keeping and breaking and making of law. We are bringing Witness to bear on action, making it clear that Agency is always in the presence of Witness. Interpretation does not follow on from behaviour. They are both carried on performance.

c) I have put three words at the point where the axes intersect so as to place a) risk (stake), b) the affect associated with risk (gratuity), and c) the cognitive response to risk (probability), at the centre of our field. If the model is to act as a compass rather than a grid, it is this mixture of affect and cognition which enables it to turn, and gives it direction. I am trying to suggest that the circulation of energy and attention between judgment and making depends on affect and cognition of a special kind, the kind associated with risk.

I have chosen the word stake rather than risk for the central position because it allows for both an active and passive sense of time.

For over twenty five years I have been arguing for more discussion of the costing of time in psychotherapy and counselling. Some of the most important disagreements within the profession are about time. How is the public to have its say when we are so divided among ourselves?

The costing of time has to be accepted as a problem in its own right. It is not only a question of money, though money enters powerfully into it. In being human we are thrown into time, and also obliged to establish some kind of hold on time.

Time is given into our keeping. Lifestory results. In soliciting transference we take on lifestory. We solicit expectation, and the fear that goes with it, about both the being thrown into, and our ability to get a hold on, time. The idea of stake can help us own, to ourselves and with our patients and clients, such expectation and fear and to consider in what ways we are equipped to deal with them, whether through action, through letting be, or a change of mind.

Stake is a word with a wide range of associations. (Remember please that what follows was first written before there was talk of a stakeholder society.)

Some of these are religious. Person and world share together in the hazard of creation. Other associations are aesthetic, and speak directly into our work with the dramatic model. Others are reminiscent of the commitment to proof by experiment on which modern science lays such emphasis. Proof can hurt. When Francis Bacon spoke of ‘putting nature to the torture’ proof in law was still a burning matter. Others are more redolent of the gambling table, of the stock exchange, of the peculiar conjugation of investment, debt, risk, profit and loss, in a market economy, whether that market be thought of as internal or external. Others remind us of crime and its detection, of those acts which we may be called into court to answer for. They all place us, irrevocably at risk, in a world which is itself at risk.

A stake is something we can stand surety for, and redeem. It speaks of interdependencies which are commercial, legal, religious. Lifestory is full of them. There are investments which we can sell, disinvest. And there are investments which we are locked into, investments that turn into debt, negative equity that we experience as thoroughly inequitable. Risks can payoff. Or they can land us in debt.

It helps to compare risk with promise. Promises assume risk as the medium in which they work. They are made to be kept, but may not be. If they can’t be broken, they aren’t promises. Just so when we stake. We are willing to go for broke. It is our willingness to risk going broke that locks investment into the real world.

When we throw or put down a stake we personalise chance. One of the not talked about enough dilemmas in psychotherapy and counselling is what we do with such everyday human experiences as chance and accident. In one way or another I suspect that we invoke something like fate or luck or providence, or allow our clients to do so, much more often than we admit. Putting ‘stake’ at the centre of our field of study helps us own what we are doing. In staking, the personal chooses to be involved with powers beyond personal control. Having chosen, that choice is no longer at our disposal. But it is still with us, and continues effective. That is why we can address our fate as we would a person.

Similarly, in being put at stake we are given value and exposure that are not ours. But they are made ours, ours to enjoy and to suffer. In a sense both the value and the exposure of the stake is always another’s. They remain beyond our means. I know of no way of talking about this without reference to God. Which is dangerous, as well as embarrassing. We have learned this to our cost. But I think we are learning how it can be done, and with the help of our public may learn better. See the paper on Psychoanalysis and Religion.

A stake is also an all or nothing. Win all, lose all. A recurring problem in our work is the too big, the too small. On the one hand, omnipotence and delusions of grandeur. On the other, impotence and a conviction of inferiority. Here maker and made confront each other across what can seem an unbridgeable gulf. But if ‘to make’ partakes of ‘to be at stake’ there are ways, familiar ways, familiar as mood and character and temperament, by which that gulf can be negotiated. The all or nothingness of a stake is not simply a question of too big, too small. It is a question of how we manage our investment in make up.

d) Here I want to bring in the other two words, gratuity and probability, at the centre of the third diagram. One is there to identify the affect associated with risk, the other the cognitive response to risk. Together they allow us to work on what may be our biggest and most difficult task: how to relate our new understanding of evolutionary inheritance with here and now experience of what life is about.

To stake is gratuitous. Being at stake we are subject to gratuitousness. The great dicing scenes in the Mahabharata celebrate this. I think also of the many creation myths I have enacted in Sesame workshops. Christian teaching has made much of the concept of grace, of the gift of grace. I prefer the word gratuitous. It allows for suspicion. It reminds us that a gift can be unwelcome, even insulting, and admits the quirks of inheritance.

Like inheritance, what is gratuitous can be cause for gratitude. But it can also be cause for resentment. It presumes too much. It is unasked for, uncalled for. It can be unnecessary. Or a trick to get us in debt. We want to protest but are reluctant to do so for fear that our protest gives gratuity an importance it does not have. Yet without such protest how do we own our resentment at the presumption of gift? It seems to me that stake allows for protest in a way that gift does not. Giving can be so careless, so reckless, so condescending, that the only way we can receive it is to treat it as a stake, to insist that what is given is simply gratuitous.

Probability is the word with which I try to identify our-cognitive response to risk. Like gratuitous, it is a word which looks in more than one direction. It combines the subjectivity of belief with the objectivity of events. Its history has two roots. One was connected with the degree of belief warranted by evidence. The other was connected with the tendency, displayed by some chance devices (knuckle bones, dice) to produce stable relative frequencies. If we can bear both of these senses in mind it helps in exploring how, in taking risks, in being put at risk, we are a) caught up in the world, in debt to the world, and b) enabled to be effective.

Probability theory is where beliefs and events are tested against each other. It accepts that this testing is both enjoyable and dangerous, and is aware that this mix can appear disreputable. But it is nevertheless willing to use this mix cognitively. Our profession needs more of this kind of cognitive confidence.

It works together with gratuity. For some years I have found myself using the phrase ‘entertain the possibility that’ with my clients. I am asking them to give time and room to the possibility that so and so may be the case. Entertainment is gratuitous: to open the door to and make welcome, give refreshment to, a guest, but not to expect, or feel obliged to expect, that the guest will become resident. Rather, to expect otherwise. It is as if two obligations meet: an obligation on the host to entertain, and an obligation on the guest not to assume permanence of tenure.

That is how probability deals with the mix of belief and evidence. Doors open to close.

Doors close to open. The possible is entertained. Evidence is recorded, but witnesses can come and go. Evidence is not fixed. It remains free to surprise. Conviction is belief in action, not cause for closure.

This implies an open textured state of mind. In allowing for risk, probability recognises consistencies which include both cause and chance. Cause and chance are made permeable to each other. We find ourselves operating as it were on a new frequency, so that what is accidental in our lives fits with those more stable relationships that we have learned to rely on as causal.

Risk allows for belief in an inventiveness out there which we are willing to let work on us.

This open textured state of mind is friendly to the body. It allows access to the body’s imagining of itself, as I have learned from psychoanalysis (for which I am indeed grateful). It is ‘humorous’ in the old sense of the word which assumed the oneness of body and mind. The body, with its gratuitous excesses, is a constant reminder of mind’s obligation to entertain and to be entertained, of the necessity for theatre. Sickness, pain, mortality: the body knows well that this obligation to entertainment is itself carried on risk. Which is why our body’s lifestory is both blessed and cursed with promise.

The inventiveness present in the play of probability between cause and chance is essential if we are to let be. It can be experienced as a kind of doom. The thought of fate as a game of dice played by gods at the expense of humanity is familiar, and sometimes even welcome. But such inventiveness can also be experienced as a call, a call not only to take risks but to put ourselves at risk. We have to find our way, apprehensive of both doom and call. This diagram is an attempt to show how we go about finding that way. But it has to be used as a compass. It gives us direction in giving us a turn.

e) The other words I have written on it are there to suggest how this turning works.

Remember what we are trying to do here. I want to picture a meeting place where professionals and their public can argue issues that are medical, legal, religious, educational, aesthetic. So I am trying to picture the way lifestory and its telling rotate round the central predicament of risk, approaching it from various positions (bearing in mind the overall need to allow for our three modalities while engaging with psychoanalytic suspicion of the Author).

I have chosen words which refer to behaviour as well as to insight, letting be as well as intervention. I am trying to place psychological insight in a social, historical, behavioural, context that is ‘eventful’. I want us to be able to picture our part in ‘the turn of events’, in ‘the ways things are’, to understand ourselves as making acting judging witnessing, rather than focus on the relation between consciousness and unconsciousness.

Reading clockwise from the Maker (Author) position we have experiment, question, suspicion, regret. I am trying to show how we may be more familiar than we realise with the ways in which judgment can bring the maker gradually to regret its creation. Reading anticlockwise we have minding, appeal, conviction, separation. I am trying to show how judgment can bring the maker gradually to separate from her creation, letting it be. By placing experiment and separation, question and conviction, suspicion and appeal, regret and minding, back to back as it were I want to get us thinking about the Maker’s confidence (or lack of confidence) in his making, and how we experience this in the daily and nightly ‘turn of events’.

By doing so suspicion of Author (Maker) is brought into play. We can be suspicions of Author without excluding ourselves from the Author position. Suspicion enables participation without identification. In recognising the special kind of risk entailed in making, risk that implicates willing and believing as well as knowing and doing, we can allow for authorial presence without identifying with it. Performance (behaviour) comes into its own in contrast to insight. What psychoanalysis can dismiss as acting out is often simply our ability to cross performance with letting be, showing that doing can be its own best interpretation.

The four words along the axes describe our lifestory’s more general responsibility for, and ability to respond to, risk (risk as debt, risk as opportunity). We throw and are thrown, we catch and are caught, we weigh and are weighed, we wait and are awaited. To own risk both affectively and cognitively, to admit it as something to which we can feel both indebted and grateful, we need to be researching activity and passivity of this kind. Regulation of transference solicitation has to include research of this kind.

Which is asking a lot.

Consider for instance the word trust. To own the risk of creation, a risk which is both debt and responsibility, we have to be able unpack the word trust. It is one of the most urgent tasks facing our profession. In looking at this diagram I am asking you to see, arranged round its centre, an invitation to question what we mean by trust. To throw and to be thrown, to catch and to be caught, to weigh and to be weighed, to wait and to be awaited: how do they relate to what we mean by trust? There is no way of understanding the risk of creation, which is also the creation of risk, without questioning our experience of trust.

There is a pool, an unfathomable pool, of experience here. But the pool is not still. It is in a constant state of movement, movement which turns on choice, on the freedom of choice.

And with that word freedom we come close to the heart of the matter, to the incarnation of risk.

There is no trust without freedom. And no freedom without fear. Questioning our experience of trust opens us to our fear of freedom.

These four words round the centre of the diagram are therefore to help us map a field of choice which recognises our fear of freedom so that we can work with it.

If our public are to have a say in the regulation of our profession, as they already have in its running (they keep us going with their money), we have to be able to talk together about our fear of freedom. What is needed is a culture in which people can explore how our experience of trust, and our fear of freedom, work with and across each other. That is the culture we should be working together to create.

The first three diagrams together

To do so we are all going to have to learn a more vulgar (common) language. I think we are going to have to talk, commonly, about spirit, mood, weather, atmosphere, however unscientific such words may sound.

Spirit allows us to draw breath. That’s why we have to use the word. Because it is breath which gives language to body, body to language. And it is that connection, the connection between body and language, language and body, that we have to keep in mind if we are to talk with our public about the incarnation of risk.

Words to do with weather are helpful in realising what is at stake here. They make the all important connection between spirit and mood. If we and our public are to argue together we must allow for the climate of opinion, those changes and settlements in the mood of society which make some things sayable, others not. When we solicit transference we are helping to create an atmosphere. Regulation in which our public participates will have to allow us all our part in the creation of the atmosphere which we breathe.

Between us and our public atmosphere of a new kind is trying to ‘set’. That setting is always going to be uncertain, uncertain as the weather. It is apprehensive. We have to allow for the shiver of apprehension. It is how suspicion is brought into play. It is what talking with our public is always going-to be like: prickly, ticklish, nervous.

As so many have said, spirit is like breath and fire. It is free to blow like the wind. It takes hold like fire. (It can also fan flames. That is a danger which these notes do not address.) In talking with our public about making and being made we have to allow for both, the freedom and the taking hold. To entertain the possibility that we and the world are made, we have to be able to allow for the freedom of the maker and the seizure (arrest) of the made. Talk of spirit allows us to do so. Spirit is there when we allow for the difference between maker and made.

Or perhaps it is more exact to say that spirit is there when we can allow for the difference between maker and made.

This is why it seems so important to insist that the crossed axes in my diagrams must not to be collapsed into each other. Drawn like this they remind us that cross examination, which is what some of our patients want to be able to do with (or is it to?) us, turns between making, acting, judging, witnessing. In allowing for the difference between maker and made we are rightly suspicious of Author. We suspect it of presuming too much, of being too sure of her powers. But that suspicion has its own unease. The question niggles: why not let Author have his say? Spirit as I understand it allows both for suspicion and for its scrutiny. It allows questioning to be effective but is always alert to question the questioner.

Questioning the questioner: is that a regression without end?

No. Spirit, like breath again, knows both inspiration and exhaustion. There is filling and emptying, giving and taking away. Between us and our public there is room for both.

This is what I have in mind when I write of a circulation of energy and attention, of movement between active and passive verbs, of staking and being staked: the breathing of the body. Spirit alternates like breath. It is by allowing for alternation that it is constant in questioning the questioner. The in and the out make way for each other. We gasp, and we catch our breath. Spirit is in both. It allows for a texture to experience in which we can get caught and still find ourselves free to gasp: in wonder, or in protest, or perhaps simply because it is just too ticklish.

I wrote of an open textured state of mind which recognises consistencies that include both cause and chance. Our throwness into time calls up our responsibility to get a hold on time.

When chance and cause are permeable to each other, surprise and habit can play on and across each other. If the public are to participate in regulating our profession that play is going to have to create its own atmosphere. We must have air that we can breathe in common. But we disagree on important issues. To join in argument (‘join’ rather than ‘fallout’) we are going to have to allow those disagreements to set their own weather.

Here I think a fourth model may prove helpful. The culture we have to create together must have more “we” mixed in with the “I”. We need a picture of how problems that are private, personal, individual, are also, essentially, public.

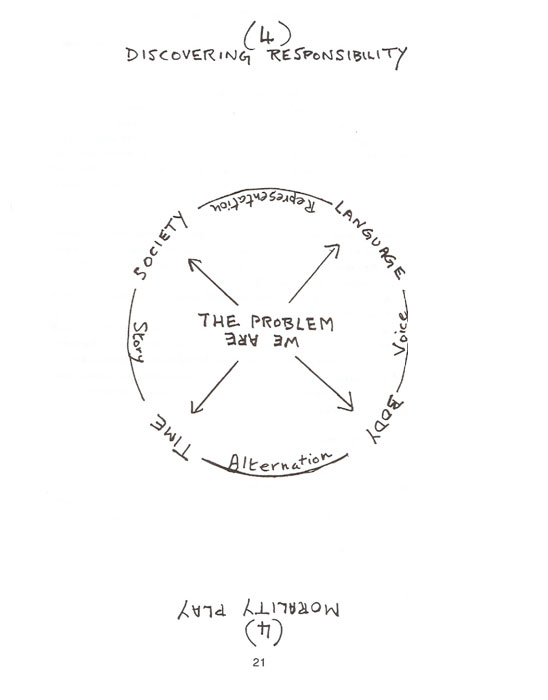

Fourth diagram: Morality Play, or, Discovering Responsibility

Let us play with the word responsibility. Let us agree that it can sound more open than it usually does. more like response ability.

This model has developed from my reading of Barry Unsworth’s novel Morality Play.

Unsworth tells a story set in late fourteenth century England. a time of war and plague. A group of travelling players arrives in a town intending to perform one of their stock of traditional plays. But the town is engrossed in a drama of its own. A young woman is to be hanged for the murder of a twelve year old boy. Partly in order to increase their takings, the players get drawn into making a new play, to enact the murder of the boy. But as they rehearse, they find themselves caught in the plot of a story that has still to work itself out. As it does so. it is as if the presence of the players enables the town to resolve its own mystery.

Morality Play is a good read in its own right, a gripping detective story. It is also a description of how what we think of today as theatre emerged out of other kinds of social thrown togetherness. As I read it, I found myself thinking again and again of my dramatic model. and I began to experiment with rearranging its various positions. I was trying to picture how a community (Audience) such as the town in Unsworth’s novel, burdened by some terrible plot, might generate such an atmosphere that it, the atmosphere, could call up Players, and behind the players an Author, so as to allow a Performance that would free them of their burden. Instead of the play originating with an Author, here it originates with the Audience.

Author is commissioned by Players on behalf of Audience to find words for the plot in which all are caught. But as I worked on it, I realised that what was happening was a much more radical revisioning of my whole dramatic enterprise. It was as if my model was reworking itself so as to emphasise “We” rather than “I”.

What I have come up with is this.

At its centre, we are the problem. Think of this as the dawning of a vague inarticulate sense, or as a sudden clarification. It occurs in the growing child. or in the remoteness of our evolutionary past. It seizes on the adult in the moment of religious or political or vocational commitment. Whenever, the problem is us. Not just with us, or about us, or in us. The problem is us. We are the problem.

Then I want to picture a throwing and a catching.

The centre explodes in recognition that we are indeed the problem. The exploding throws (projects) us into Time. Body, Language, Society. Between them we are caught. Being caught, we are able to respond.

The space within the diagram is not empty. It is charged. If we and our public are to talk together we need an atmosphere, a culture, that is charged with recognition that it is we who are the problem, and it is we who are able to respond. I am trying to picture this response-able, charged-with-weness, atmosphere as energised by a throwing and a catching.

Approach it through feeling. Ask yourself what it is going to feel like in the room when we try to talk together about what was once confidential. We are trying to find words that can research privacy in public, recall events that have broken hearts, frozen minds. so as to present them to the We in which I find myself. This is the move from protection to participation. It is a big move, a radical adaptation to a changing climate. But it is an adaptation that we have to make. And to make it we are going to have to combine the feeling that we are all caught up in something hugely bigger than ourselves with willingness to experiment. to submit to lest by trial and error.

This model is an attempt to picture such a combination.

When a patient wants to challenge the work we have done the rules about confidentiality change. A new kind of confidence (and this is no facile play on words) has to be assumed. If I am to respond I have to be able to assume that he or she is claiming, rightly, a certain self confidence. What was secret is being given a new importance, a new respect, a new reference. What was private is now to be treated as typical. It refers to Us. In an extreme case, it can be said, either by patient or by professional: “Because of what was private. I am taking you to court”.

How do we incorporate this new assumption of confidence into the regulation of our profession? The climate has to change. There has to be more of “We” mixed in with the “I”. The atmosphere, the air We breathe in common which determines what can be said and what can not be said, is made up of We-ness.

As we are learning in the group therapy movement, what goes on in groups is not just an extension of what goes on in one to one therapy. It is much, much. more. radical in its implications than that. It is a reminder that We Comes before I, and that to understand what happens to me I have to first accept that there is an Us problem.

Thinking of the various patients who. in different ways, have intimated to me over the years that they Want to challenge what we did together, whether to complain of confusion over authorship, of missed Opportunity, of indigestion, or to speak their conviction that they can help me rather than I them, I believe that the atmosphere, the culture, they are wanting to create will be charged with a new agenda.

The words I have placed round the circle, facing inwards, are to suggest what that agenda may be.

Alternation and Story are both about what I have said may be our biggest and most difficult task: how to relate our new understanding of evolutionary inheritance with here and now experiment with what life is about.

Alternation: a shared commitment to time’s continuous discontinuity. How do we embody, here and now, our evolutionary calling? I am thinking of our breathing, our heart beat, of the fact that women’s bodies give birth to men’s bodies. I am thinking of the alternation of day and night, the phases of the moon and the seasons of the sun. I am thinking also of what evolutionists have done with the word ‘adaptive’, of our given overness to an agenda that is ours and not ours, an agenda that commits us to constant experiment with alternatives.

Story. The point I am wanting to make is that there has to be story. It is a point which I think the evolutionists can easily lose in conflating history with evolution. Story is how we both cost and tell time. There is a gap between inheritance and what is now to come which is both costly and telling. Our personal memories are caught in that costly telling. I cannot understand what my memory makes of my life unless I allow for our response ability for story. Story is what keeps society going, and it is in that keeping going that we have to find our place.

Voice. If our patients are to find their voices, and we a voice with which to answer, it must be agreed that voice sounds out of body, and that words, the language we share, is made out of voice. Research into my own voice production, following a mild stroke, convinces me that there is an agenda here which I for one have largely, and mistakenly, neglected.

Through breathing voice is resonant with alternation. It is, I believe, that alternation which ‘confidentiality’ is seeking. Voice is ever mindful of body. Behind the distinction between what is said and what is not said, between what can be said and what cannot be said, between what should be said and what should not be said, voice sounds the body. In finding voice together, we enter that sounding. We need meeting places in which this sounding can be heard.

This paper is about how to make this interest more explicit.

Representation. I chose this word to remind us of the theatricality of language. Language is more than description, more than communication. It does things. It changes things. Speech acts. It performs. It re-presents. Our sense of creation, of being both maker and made, is carried on this performative power of language to make present again.

There is an agenda here which needs a more public forum than the consulting room or the professional body. We talk a lot about language, about word association, symbol, metaphor. ‘When to make an interpretation’ is a key moment in our technique. But there are other questions that cry out to be aired. Interpretation can indeed change the world, but worlds can also get lost in translation. Speech acts can bind, as when parliament enacts law. Our work needs a forum that can call language itself, not just our use of it, to account. For instance, with respect to confidentiality. As we move from a protective to a participatory professional culture, anxiety about confidentiality is taken up into a more inclusive sense of shared responsibility. There are matters that are private, matters that are public. Language has to account for all. What do we have to do to make that accounting possible?

Alternation, voice, story, representation. An example may help bring the whole model to life. An elderly Christian, talking about the state of his church, suddenly says: “If I had told the truth about my sex I would never have had children”. Make a play out of that, bearing in mind that for the speaker his church is supposed to be the body of Christ.

I have chosen the words for this model (as for the others) to be user friendly. Other words can I am sure be found, and may well be preferable. Their purpose is to suggest how a charged-with-weness atmosphere can become something we can breathe, move about in, sound.

What is important is to stay with theatre. Note what has happened to the Author of my first model in this revised morality play. It is recast as representative of Us. We commission Author to find words for the plot that We are. That special ‘otherness’ of Author now serves to remind Us that response ability is there to be discovered. There is a matrix out of which individual and society, I and We, call each other into being. We are projected into, and caught by, plot. Theatre re-members, and re-presents, that plot. That is what could happen between us and our public. I say ‘could’, but it is indeed already happening. Audience is taking a fresh interest in its responsibility for Plot.

This paper is about how to make this interest more explicit

Conclusion

How does all this bear on the regulation of our profession, on how we account for ourselves as solicitors of transference?

If we remember our breathing, if we allow ourselves time in which to breathe, I think we will find that spirit regulates. There is a spirit moving between us and our public. There is suspicion to be voiced. Our public need to find their own voice in response to the risky work they do with us, and for that they need us to answer for the risks we take.

There is much talk of protecting the patient. There is less talk but perhaps more anxiety about protecting ourselves. Perhaps we are afraid of our patients. (It would make sense for us to be afraid if we are indeed up to something more than we own.) If what I am saying about risk is true, how does it go with all this talk of protection? Over the last fifteen years or so professional anxiety has mushroomed. It has generated a climate of opinion in which insurance could become an overriding concern. (I have heard of a case in which the insurer threatened to remove insurance cover if an attempt were made at mediated reassessment of work done.) Our need to be on the safe side could so influence our approach to human nature as to become self confirming.

There is another way of using fear. We can risk it being responsible. We can invite more active participation in sussing out what is at stake in creation.

I believe that a new regulatory climate is already in the making, a climate in which feedback from our clients and their families becomes part of wider public participation in our work. The complaints and satisfactions of the individual client belong with a wider public scepticism and appreciation of what we are doing. There is an argument to be joined which is about human nature and its place in creation, not about professional competence important though that is. That is the argument in which we can answer for what we are doing when we solicit transference.

What we need now is to hear from our clients and their families as to how they experience our solicitation. Work being done by the professional bodies is part of wider social assessment. The spirit is moving for dialogue that is more heartfelt, apprehensive of creation and exacting of belief. That is where the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, the ‘charisma of uncertainty’, have to prove themselves: in testing belief and creation against each other.

2 Re-Minding, Letting Be, Showdoing

1

In this paper I want to air my scepticism about analytical psychology as a profession.

So that my argument can stand on its own feet, let me begin by saying where it comes from.

First, from my interest in theatre, which began with my Diploma thesis in Zurich in 1965-6, on Persona and Actor. Theatre has given me an interest in performance which I don’t find catered for within analytical psychology. Second, from my experience at the Westminster Pastoral Foundation between 1971 and 1982. The seemingly irresistible takeover of the pastoral by the analytic started me wondering what kind of historical moment and sociological process I was caught in. Third, work with people employed by the National Health Service. There is a problem about the relation between physical and behavioural approaches to psychotherapy, and transference centred interpersonal approaches, with which it seems to be impossible to get to grips. There are times when the ex newspaper man in me finds this a public scandal. Untended, this problem can become institutionalised in ways which prevent dialogue. I want the freedom and energy to address myself to this.

Experience within the Jungian community in England has certainly contributed to my present position. I have talked about this at the Jung Club (Holt, 1986). But I don’t think I am denying its importance when I say that it has been secondary to more general pressures on me, pressures deriving from times in my life, both past and future, which aren’t in any particular way Jungian.

2

Thinking about how l would like to see psychotherapy organised and taught I have come to identify three movements or modalities. I think of these as movements of the mind and heart and intellect which are both spiritual and technical. I call them the re-minding, the letting be, and the showdoing. I believe that psychotherapy should be so organised and taught as to allow for the fullest possible exchange between these three modalities.

Re-minding is of two kinds. One is about memory, the recall of times past. The other is associative, it makes comparisons, it employs our human sense for likeness. How these two kinds of re-minding are related is a question about which we are very confused. The psychology of the unconscious has led us to experiment with the therapeutic effects of combining them, so that memory is enriched by metaphor, and our powers of mental comparison and association are energised by story. Much remains to be done to clarify what happens when we encourage combination of this kind.

Letting be is about enjoyment and suffering. It can be active as well as passive. It can sound with the deep affirmation of a religious Amen, and with the bitter note of querulous self-pity. Letting be takes things as they are. It draws on connections between habit and spontaneity, freedom and inevitability. It accommodates boredom. It is about courage, staying power, endurance. But such endurance can allow us to re-cognize, for the first time, that things are indeed as they are. This links it to re-minding.

Showdoing moves, as its awkward name implies, between two verbs, to show and to do. Show me what to do. Show me how to do it. Here, let me show you. Showdoing is bringing up children, education, apprenticeship. It thrives on demonstration. It is the properly human power that energises the behavioural sciences.

In trying to spell out the connections between these three movements of technique and spirit and what I have learned from Jung, the first step has to be to drop the term analytical psychology. In its place I shall use the expression (psycho)analysis.

The name analytical psychology had its historical purpose, clearly to differentiate Jung’s work from that of Freud, while allowing resonance with their community of interest. But if the organisation and teaching of psychotherapy is to encourage the fullest possible exchange between re-minding, letting be and showdoing, we need to be able to talk easily of the Freudian and Jungian traditions together, while continuing to own their historical differences and their abiding need on occasion to bracket each other out.

Jungians have tried to use the words analyst and analysis on their own to carry their sense of professional identity. There are times when I use them of myself. Perhaps we are now stuck with them. If so, it is a pity. Because they are wrong. They obscure those influences in his work which led Jung to prefer the term Komplexe Psychologie. They evade the question of what it is that we analyse. And in doing so, they cut corners and suggest too easy an accommodation between shamanism and accuracy.

The expression (psycho)analysis is awkward. But in being so it re-minds of awkward facts, and might make it both easier and more profitable for us ‘to wash our dirty linen in public’. (Psycho)analysis re-minds us constantly of the Freud-Jung split. We need this re-minder if we are to profit from the energies released by their quarrel. Freud and Jung are finding their respective places in history. Ignorance of Jung in the Freudian tradition continues to be surprising if not scandalous. We need places where the study of Jung is encouraged and furthered. (I am struck by the way I have returned to the close study of Jung’s books since publicly distancing myself from his profession.) But in teaching psychotherapy, in training psychotherapists, we have to be reaching out for a language that can comprehend both traditions without denying the reasons for their falling apart and the many ways in which ‘we have benefited from the consequences of that parting.

(I don’t think I am saying anything particularly new here. My Zurich training in 1961-6 included extensive study of Freud. Most contemporary practice and writing in analytical psychology assumes the need for sustained interest in the work of Freud and his successors. What I am saying is that it would stimulate more searching study of Jung’s books, and more fruitful debate with other traditions, if what we called ourselves made it clear that this is what we are up to.)

3

We use re-minding constantly. ‘Does it re-mind you of anything?’ ‘What does it re-mind you of?’ Re-minding is how we explore, probe, cast about for a scent, amplify, call up a context. What is peculiar to (psycho)analysis is the emphasis placed on the concept of the unconscious in trying to explain what happens when we are re-minded of. Although there are different theories of the unconscious, they all have in common an extensive use of vocabularies of knowing and awareness, unknowing and unawareness. If we submit to them we become immersed in a language world in which mind is assumed to be about knowing and unknowing, awareness and unawareness. Other views of mind are blanketed out.

There is a perhaps rather old fashioned English expression: ‘that puts me in mind of’. People do sometimes use it instead of ‘that re-minds me of’. It is worth thinking about: the verb to put, me as object of an action, and mind as both a place and an attribute, the ‘what’ in which I am put is ‘of’ something else. We have here the intentional or object-relatedness character of our mindedness.

Is this kind of mindedness best thought of in terms of consciousness and unconsciousness, or is it better thought of in terms of being and doing? How does mind as a ‘knowing or relate to mind as a ‘showing up’, an ‘acting on’, a ‘doing to’?

We can approach the question through ‘interpretation’. Problems of interpretation figure prominently in the history and current state of (psycho)analysis. They move between what I am calling the three modes of re-minding, letting be, showdoing.

(Psycho)analytic interpretations make extensive use of sign, symbol, metaphor. Some of our most deeply felt and enduring separations have been occasioned and sustained by differences in understanding of how one thing can be ‘like’ another. There seems to be a need for fairly small groups sharing agreed assumptions as to the nature of metaphor, who can work intimately with each other in scrutinising the use of likeness, and in developing a teachable approach to how to use similarity, resemblance, representation, to effect psychological change. There is also need for these groups to be able to converse together. When this is successful, it is because we are able to suspend belief in our acquired metaphoric habitat and to entertain the possibility of other ways of experiencing and applying likeness. We move from a first degree intimacy with the uses and abuses of symbol to a more suspended state of metaphoric animation within which it may be possible to compare what works for us with what works for others without agreeing with them. (It sometimes seems as if it is impossible to sustain such a state of suspension without losing our ability to make metaphor work in our clinical practice. There are case discussions which can be physiologically deeply disturbing (as well as perhaps in some unacknowledged way exciting) but which can make it very difficult to go back into our practice the next day.)

But (psycho)analysis also uses interpretation in situations of what we call transference and countertransference. I think the organisation of psychotherapy would be improved if we learned to study transference and countertransference in terms of what I am calling showdoing. This is already happening through the influence of group work and family systems work on (psycho)analytic satisfaction with traditional approaches to one to one work. Listening to some of the more relaxed, off the record, exchanges between (psycho)analysts when they meet in a shared interest in ,theatre I hear talk of transference and countertransference which seems to me to herald a root and branch revisioning of (psycho)analysis as we know it.

The distinction between showdoing and re-minding in our approach to transference can be approached through secret. For re-minding, secret is something to be got at. If I am ‘to be put in mind of’ a secret there are codes to be broken, clues to be solved, pretences to be seen through, riddles to be guessed, censors to be outwitted. Working with a secret is a progression from the known to the unknown, so that what is unseen becomes seen, what is unspoken is said.

Within the showdoing modality, secret is in play between the two verbs. We apprentice ourselves to learn the secrets (or mystery) of a craft or trade. We apply for the master class to learn the secrets of performance. We are accepted for the class if we are judged to have what it takes, to be able to use what is going to be shown to us. The secret is ‘for showing’. What makes it inaccessible is the way it is lodged between a showing and a doing. There is a ‘show me what to do’ and there is a ‘show me how to do it’ to which all education is a response. The secrets of adaptation, of learning, of skill, of culture, are lodged between the show me what and the show me how. That lodgement is got at in doing.

What (psycho)analysis sometimes seems to be trying to do is to persuade us that this showing and this doing can, and indeed should, be defined in terms of knowing. The power of (psycho)analytic discourse, its attraction, its fascination, its outreach and its inscape, its ability to convert and to make what began as a method into a way of life, these are all generated between words of knowing and unknowing. A language of consciousness and unconsciousness turns with missionary and colonising zeal on all human life as its domain. Showing and doing are translated into problems of knowing and unknowing, and secrets which could be dealt with simply if showdoing were allowed its proper function become the stuff out of which strange, expensive and sometimes exhausting tapestries are spun. As a cultural phenomenon it is amazing. I doubt if from within it we can even begin to imagine the aberration we may be caught in.

Or perhaps we are beginning to. Take the last two paragraphs of the Laplanche-Pontalis discussion of ‘Acting out’.

One of the outstanding tasks of psycho-analysis is to ground the distinction between transference and acting out on criteria other than purely technical ones _ or even mere consideration of locale (does something happen within the consulting room or not?). This task presupposes a reformulation of the concepts of action and actualisation and a fresh definition of the different modalities of communication.

Only when the relations between acting out and the analytic transference have been theoretically clarified will it be possible to see whether the Structures thus exposed can be extrapolated from the frame of reference of the treatment – to decide, in other words, whether light can be shed on the impulsive acts of everyday life by linking them to relationships of the transference type.

To clarify the relations between acting out and the analytic transference we are going to have to demote our words of knowing and unknowing and allow the verbs to show and to do more power and more room. What we expect of interpretation has to be able to allow for the different modalities of imaginal likeness and physical representation. Criteria on which the distinction between transference and acting out can be grounded will have to take into account what theorists of the theatre call ‘deixis’, the energy released when persons and objects on a stage point at themselves. Deixis is what energises theatrical presentation. But it also energises all behaviour-in-a-context. It is not something to be got at by interpretation of an imaginative, reflective kind. The interpretation it calls for is, quite simply, performance. (Holt, 1987).

Sometimes it seems as if (psycho)analysis just forgot this. It is as if somewhere along the way . we met with someone who persuaded us that the secret of the performance was to be found in knowing what to do and we could dispense with any showing. So for many years we went in search of that secret in lands where the only performance of interest took place between our knowing and Our unknowing. Then we remembered something called object relations, and suddenly counter-transference was as, if not more, interesting than transference. Showing is become important again. Behaviour can point to secrets more economically than reflection, meditation or exegesis. How to energise that pointing is an important question for psychotherapy. We’d learn more about it if transference work and behavioural studies could find ways of talking to each other.

The energy of such pointing is close to what I mean by letting be. Performance is active, demonstrative, interpretive. Its interpretations – in the theatre, in the concert hall, in the workshop – are always open to another go. There is always room for another try. But they are nevertheless complete in themselves. They stand or fall on what is shown in the doing, done in the showing. There is a concentration of effort that is content to let its case rest.

This ability of performance to let its case rest is something we are going to have to think about if the behavioural and interpretive sciences are to learn from each other. What does it tell us about the relation between action, interpretation, and being-minded-of? The answers I work with have to do with letting be.

Like showdoing, letting be moves between two verbs, to let and to be. It is about permission, both in the sense of making possible and of leaving alone. And it is about what there is simply no other word for than Being. Aristotle called it ‘that which is’, Wittgenstein pointed to it with his remark ‘Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that the world is’. Being. The given presence of what is. The verb that sustains all nouns and adjectives that we can think of.

How ‘to let’ and ‘to be’ are related is a constant question in living. It is one to which psychotherapists have to address themselves in every consultation. The course I started at the Westminster Pastoral Foundation on ‘counselling and ontology’ was an attempt to work out how this could be taught. I abandoned it, faint of heart, in the face of the seemingly irresistible attractions of the (psycho)analytic alternative.

Teaching how to let be brings us into conflict with re-minding. The crucial point is that while being-minded-of can often assist at the recognition of Being, it can also work against it. Experience with counselling and ontology has convinced me that feeling is at stake here of a kind which the (psycho)analytic schools simply do not comprehend, (though perhaps what divides them does). We must try and get this feeling into the organisation of psychotherapy.

If we give ourselves over too much to re-minding we can find ourselves possessed by a spirit which knows no rest. The cultivation of memory, symbol, metaphor, imagination, becomes an addiction which cannot let be. At its best, re-minding is a call to explore all available likeness. But if we follow that call we must realise that likeness has no reason to let being rest. Likeness is restless to translate, to transform, to compare. It is impatient of the givenness of what is. It finds something defeatist in ‘that is how things are. So be it’. It knows there has to be a behind and a beyond and a besides. There must be a way through or round. How things are is always open to conversion.

(Psycho)analysis has appropriated this restlessness in the presence of Being, and intends to make of it a profession. The strategy is in two stages. First, to harness this restlessness to our unknowing. This can lead in very different directions. depending on how unknowing is defined. If, with Jung, there is a tendency to identify our unknowing with the ground of Being, it can lead towards an enlargement of symbolism at the expense of Being. If, with Freud, our interest is in unknowing as denial and privation, then it leads towards what Paul Ricoeur has called a ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’. All attribution of meaning is suspect. Being is left alone. Its grounding is not presumed on. (Which may come closer to true recognition of Being than the Jungian way, which sometimes seems perilously close to a collapse of ontology into symbolism.) But though the directions are different, the essential strategy is the same. Unknowing, as a kind of resourceful absence awaiting cultivation, is harnessed to our restlessness in the presence of Being. Our unknowing, our unawareness, is what carries the theoretical and practical weight. Doing and showing are of interest only in relation to states of mind, so that re-minding becomes an activity in its own right.

The second stage is to apply this activity to our own life story. A special kind of telling-about-ourselves is generated. Our ability to re-mind, and to be re-minded, is brought to bear on our partial knowledge of our story. The fact that we are ignorant of most of our story is taken as a resource. Inexhaustible ignorance of our infancy and childhood is played off against ignorance of a future which is still to be revealed. A two way dynamic, like a pulse, is set going. In drawing on ignorance-as-resource we exercise our ability to be re-minded of. And in exercising that ability we confirm the resourcefulness of unknowing. We begin to feel that we are getting inside the generation of our own story, becoming pregnant of our own cause. It is as if we get in between cause and effect in our lived story, and in gradually discovering what they have in common begin to feel the beat of a secret pulse, the pulse which causes my life to be as it is.

The result can be fascinating. It has created an absorbing profession, albeit a profession which can be quite extraordinarily rude. It can appeal to the same sense of discipline and self sacrifice as has inspired great spiritual and ethical movements. It has an effect far beyond its own borders, not least among other hermeneutic disciplines concerned with the discovering and keeping of secrets. But what does it do to our ability to let be?

Letting be can be mute resignation. It can be world weary cynicism. It can be resentment; resentment that eats into the soul, hardens the heart, exhausts the spirit and paralyses the imagination. Yet it can move from that to a position where ‘making do’ is possible. Make do and mend. There can be a moment of relaxation in which amendment and compromise become possible. We say, ‘Oh, let it go’, and a hopeless argument in which we are stuck moves into conversation and exchange. We say, ‘Well, yes, I can live with that’, and signify a willingness to take what is given as making a fresh start. How is such movement possible? How is it helped and hindered by re-minding?

4

We have to think about time (always remembering that to think about time truly requires that we tread tenderly, for we are stepping on the wings of butterflies). Ontological tradition teaches us that respect for Being goes together with puzzlement about time. To understand what (psycho)analysis does to our ability to let be we have to ask how (psycho)analytic causality relates to what I have called the consistency of time (Holt 1982, 1987). Are the causes which (psycho)analysis searches out and recapitulates to be found in time, or are they also, or alternatively, of time?

I have spent much effort in the last twenty years trying to air questions about time in Jungian circles, with little response. I confess to being surprised at my failure. I would have expected a community interested in a concept like Jung’s synchronicity to be more.. eager to enter into debate about time. I begin to suspect that (psycho)analysis as a whole may depend for its existence on a collapse of metaphysical time-questioning. Which would be a pity. Because (psycho)analytic research into sexuality, and particularly into the relation between sexuality and death, is itself calling urgently for a re-awakening of just such questioning.

The causing of time is all round us. We celebrate it in worship and prayer and festival. We drawn on it in hope. We invoke it in promise. We struggle with it between the generations, as we measure up to each others’ vitality. It permeates social intercourse. It is like the sap in what sociologists call ‘the social construction of reality’.

(Psycho)analytic theory is very weak on the social construction of reality. (Psycho)analytic practice is constantly trying to make good that weakness. Work in groups and families reaches out towards recognising how persons are socially constituted. Many (psycho)analysts realise that here lies the challenge, if not the crisis, of their future (see, for instance, the urgency of Isabel Menzies Lyth in her interview for Free Associations, No. 13, 1988).

Work of this kind would receive a great impetus if it were to allow for the social causation of time. This is indeed meta-physical, but not in some pejorative sense of inaccessible rumination. It is, as I have said, all around us. In 1985, Channel 4 Television in England carried an excellent series of programmes on its ‘all around us’-ness. The Series Consultant, John Berger, wrote of the intention behind the programme:

It wasn’t that we thought we knew what ought to be said. We have all discovered the trap which St Augustine described so succinctly: ‘What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; but if I wish to explain it to he who asks. I know not!’

No. it wasn’t that we knew what ought to be said. It was simply that, through our different experiences and lives, we had come to the conclusion that the notions about time which are embodied today in formal education, the current assumptions of news bulletins, political promises and moral sermons, are patently inadequate. What we wanted to do was to clear a space that could be given over to other, more intimate, less rhetorical and more far seeing intuitions and questions which cluster, for the most part unacknowledged, around everyone’s experience of time, and then to let these intuitions talk with science and history.

To clear a space…. The organisation of psychotherapy as a profession needs such space. If we are to understand what (psycho)analysis does to our ability to let be, how it can undermine it with the concept of the unconscious and then dedicate itself scrupulously to its rediscovery, we must set it within an organisational context which does justice to the intimate and far seeing intuitions and questions which cluster around our everyday experience of time.

It helps to imagine what such a context would be like if we think of our problem with ‘how many times a week?’ Will it ever be possible for five times a week and once a week (psycho)analysts, and all the positions between, to talk to each other truly?

One of my most marked experiences of (psycho)analysis has been of the peculiar unease when any attempt at such talk is made. There is a strange feeling of discomfort. It is as if what we are trying to talk about is in bad taste. Value systems are being compared in a way that threatens dishonour.