The Clermont Story: arguing christian responsability by David Holt

Contents

Introduction

PART I – CAUGHT BETWEEN HISTORY AND NATURE

1 Responsibility Gone Missing

2 Clermont

3 Rudery and Mystery

4 Flailing and Flaying

5 Tudor Sexuality

6 Personality

7 Zurich and the Theatricality of Being

8 1st paper: the Yes and the No of the Two Virgins

9 2nd paper: Sado-masochism and the Peculiar Numinosity of Machines

10 3rd paper: Repetition of Repeated Reversal

11 4th paper: Apocalypse and the Invention of the Method of Invention

12 5th paper: A Special Kind of Curiosity

13 6th paper: Offence that is Unspeakable?

14 Dad’s Historical Holies

15 The Dove and the Boar

16 Funeral

17 Cambridge

18 In Front of the Children

19 Lenten Voicework

20 Laughter at the Foot of the Cross

21 Surprised by Gender

22 That Penis Again

23 Publishing my Dreams

24 God

25 Masturbation

26 Facing Likeness

27 Skin, an Indispensable Viscus

28 Fresh Argument

PART II – SIX PAPERS: TRADITION, PROTEST, PROPHECY

1974 Jung and Marx: alchemy, christianity, and the work against nature

1976 Sado-masochism and the peculiar numinosity of machinest

1981 Jung and the Third Person

1983 Riddley Walker and Greenham Comon

1988 Alchemy and Psychosis: curiosity and the metaphysics of time

1994 Sacred Hunger: exponential growth and the Bible

On September 11th, 2001, the final draft of David Holt’s conclusion to The Clermont Story arrived through the post. (Clermont, incidentally, is where Pope Urban II preached the first crusade in 1095). A few hours later, two aircraft crashed into the World Trade Centre, and another on to the Pentagon. The Twin Towers collapsed and the images which we watched on TV seared into the psyche with symbolic power.

Coincidence? Of course. Synchronicity? Without doubt. But what does that mean? What is the “added value” of that concept? Jung speaks of the simultaneous occurrence of two meaningful but not causally connected events. Since synchronicity has been throughout the feeling-tone (as David would put it) of my connexion with The Clermont Story I will return to it later. But, put briefly, if you want one book to understand what is going on, what we are doing to ourselves and our world, this is it.

What is going on in our world? I am a rabbi, which means teacher. I teach in and out of the Synagogue, in formal and informal settings, often with Jews, but not exclusively. In the face of the holocaust, of the tragedies in the Middle East and the continuing conflicts between Israel and the Palestinians which some now see as part of a wider conflict between Islam and the West, what can I teach? Where now do we find God? When the external world is so chaotic, how do we find meaning, or purpose? But formulating the question in this way suggests that there is an external world entirely independent of our psychological perspective, though it is also certainly true that we do not only receive but also create our world. There are ontological questions here: the very formation of our thinking and understanding is at stake.

The Clermont Story explores these issues and in particular, its purpose is to start fresh argument between christian and non christian. “To take [this] up christian and non christian have to enquire together into their differences”. (p. David throughout spells christian with a small c).

One immediate response to September 11th, written the day after, pursues such themes:

To Islam, America seems to represent the presence of the demonic in the world. To most Westerners, Islam is a huge and shadowy unknown with a few markers of custom and practice that run directly counter to our standards of pluralism and human rights. The world is presently divided into polar opposites, each of which considers the other benighted and evil. We need much greater consciousness of nuance, or points of agreement, of shared values and concerns as well as considered reflection of the meaning of wide differences. (1)

In the face of globalization, this, of course, has to be a world-wide enterprise extending far beyond the relatively cozy world of Jew, Christian and Moslem, the Abrahamic faiths. It is now unavoidable, if we are to avoid increasing chaos and disharmony, that world religions and political leadership meet and reflect deeply together. But if even these three Abrahamic religious traditions are locked once again in murderous conflict, surely it is grandiose to look beyond: and what does “reflect together” mean?

It is here that The Clermont Story is so vital. Often when we feel lost and split apart, we ask ourselves in what sense do our lives have meaning? Or purpose, or value? Sometimes, we look for answers outside ourselves, as if they were to be conferred upon us by God, or the Universe, by a priest or rabbi or, most dangerously perhaps, in the unquestioned assumptions of our secular age. At other times we imagine that such understandings are purely personal and subjective, and that we can only gain purpose or meaning in what we do, in our family life, in who we are. We then dismiss our findings as purely subjective, our own – ephemeral, fleeting, of no real relevance outside ourselves.

A central teaching of David Holt’s life and work is that neither of these two positions is adequate: meaning, purpose, value is neither given nor made. Perhaps we may better describe the process as uncovering, finding or, perhaps, intuiting. The Clermont Story illustrates David’s interweaving of personal and political, dream and myth, history and philosophy, experience and knowledge, more fully than any other writing that I know. Events, stories, encounters, publications, life itself is worked through and then reworked to reveal deeper and fuller understandings.

There is a Chassidic story, recounted by Martin Buber in the beginning of his short essay The Way of Man. It tells of a rebbe (a Chassidic word for rabbi) observing a student, who has fasted for several days but then, aware of his growing pride in his achievements, abandons the fast. The rebbe comments, scathingly, “patchwork”. Buber recounts his dismay at his own early reading of this tale. He would have expected, he writes, that the rebbe would have been more encouraging. Later, Buber comments, he realised that the rebbe was suggesting that the deeds were a reflection of a lack of unity in the soul. Still later, however, Buber was troubled, once again, by what such a teaching would mean. As Buber uncovers the layers of his reflections upon the story, we are taken deeper and deeper into an analysis of our own life.

It is exactly this that David achieves in his writing. He makes us wonder how we are doing in our own self-understanding, and he makes it clear to us how much we miss. Buber suggests that the opposite of patchwork is “all of a piece”, and David Holt’s work shows us how life can be seen as, and become, all of a piece, not his alone, but ours.

And so to The Clermont Story.

David’s work deals with central forces which manifest in our world today, sometimes seeming quite disparate and unconnected but which he links through a lifetime’s experience and research. Marxism and alchemy, Christianity and money, the metaphysics of time and exponential growth, the work of civilization against nature. Though initially they may seem arcane and remote, bizarre in their juxtapositions, The Clermont Story rightly puts Christianity at the centre of world history. David suggests (p. ) that over centuries of disciplined intellectual questioning of the Eucharist a space opened up between mind and matter which was altogether new in the history of mankind, and that it was this space (a Jew here would think of one of the popular medieval names of God, HaMakom: the place) that made possible the scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The work is in two parts. One part, the second (perhaps to be read first?) consists of key papers (from a twenty year period, 1974 to 1994), which are both extremely simple and challengingly complex. They deal with topics which stir the roots of our being. Many of them I had known previously but when I received a first draft of this collection, I read and re-read them and immediately felt that this was too precious not to share widely. I asked David for eight more copies, which I sent to friends. Some responded, but others were overwhelmed. The mixture is so rich and varied, and potent and, furthermore, there were sixty pages of introduction which wove still more questions into what could already seem esoteric.

It was those sixty pages which captured me, however. Here was an outstanding example of Socrates’ “examined life”, where every scrap of evidence, of response, of personal and family history, of death and life, stammer, heart attack, masturbation, breathing, speaking, and, most of all, dreaming, were brought into relationship with the objective material of closely argued texts which themselves raised fundamental issues about our lives and our world. Here was a twentieth century man (apparently, but sometimes he wrote as if Neanderthal, and sometimes from a century far into the future) who could not allow any moment to escape the rigour of his attention and the work of his pen. I wondered what it must be like to live with him, and he allowed us to glimpse even at that: “Dad’s historical holies” has been the affectionate and impatient attitude of the family. (p. )

Perhaps Sacred Hunger is the most outrageous piece in the book, remaining unpublished for several years, because sensed as blasphemous? Why? It emerges, as Ted Hughes remarks about David’s lectures (2), “from real work & not riffling through the card index” (p. ): dreams of eating flesh, thirty years sharing the Eucharist and then absorbing four books, all concerned with hunger and suffering and particularly with insatiability, leading to the modern hunger for unending growth. At the heart of the paper is a concern with time, not only time passing but metaphysical time, fulfilment in time and promise, also fulfilled and unfulfilled. Further, basing himself upon Whitehead, Holt introduces the absolutely critical contradiction that science works though ultimately we do not understand why (see p. ) and connects this with a consumerism which is designed to be unsatisfying.

In some ways, this is a central theme. It concerns how christianity separates humanity from matter. There is an act, a deed of violence implicit in that separation which we, christians and non-christians, but for critically different reasons (my italics) are finding it difficult to own (p. ). Holt develops his thinking: the Holy Spirit [the Third Person of the christian Trinity] is at work in the financial markets of the world and in our manufactures, in the research and development laboratories which create new appetites and jobs as well as the goods with which to feed these appetites and justify these jobs. It is also lodged in our food chain, in the whole order of interdependencies of which hunger makes us part (pp , my paraphrase).

But the breadth and depth of his thinking is evident in his discussion, in Sacred Hunger, of Chris Knight’s book Blood Relations: Menstruation and the origin of culture (3). Here the talk really comes together. We share David’s excitement, as sex and time are here brought into relationship, and can only wonder at his interweaving of history and ethno-ontology (p. ). The world in which we live, it is clear, is not given as an objective absolute but entirely dependent upon the form in which we receive it through our cultures and traditions. This understanding leads us directly to David’s conclusions and my deep involvement, as a rabbi, with them and with him.

Christianity is right to insist that the importance of that [Christ] event cannot be exaggerated and that it effects the whole world, whether the world call itself christian or not. It is wrong in understanding that event as a redemption, a saving, of the world. On the contrary, christianity has made it possible for humanity drastically to accelerate the destruction of the world.

His final introductory extract (page : Fresh Argument) offers a serious challenge to our respons-ability for the future, and a call to which I felt drawn to respond: “I am asking for help with that argument…To answer that call, christians are going to have to admit that we got it wrong, non christians that we are living off a christian secret that we do not understand”.

It is this recognition that religious and cultural traditions are far more potent in our modern world than we acknowledge that has made me so sure of the long-lasting value of David’s life work. In the political maelstrom of the Middle East, for example, Jerusalem has been for over fifty years central in the dispute, but only in the breakdown of the most recent talks did it become apparent that, quite beyond the understanding of the political leadership, the place of the Temple Mount itself has a continuing significance which overcomes political rationality. There, Jew, Christian, Moslem are joined in bloody re-enactment of ancient rivalries which we may well only be able to break with the help of a global religious forum, and, maybe, the telling of dreams.

David Holt helps us see why this may be so. But he does more: he shows us the power of the individual whose personal work can also bring about redemption. We can make a difference and we do have, as he puts it, respons-ability for the future.

As a Jew, I am challenged by David’s writing to acknowledge the negative side of Jewish exclusivity and chosen-ness, the emphasis on the family which has kept others apart. I need to re-examine our understandable sense of victimisation, our attitude to conversion and to Jesus, whom Buber called “my great brother”. But given the extraordinary strength of the synchronistic happenings which have entered into our relationship, I need also to ask: How can this be, what is the mechanism producing such synchronistic events? David’s work leads us to ask whether we do not, in fact, phrase the question falsely. We might rather ask: how can it not be?

The question is, most centrally, how it is that we are not constantly overwhelmed by the layers of meaning and richness that are potentially present at every moment. In order to function, we narrow our focus. As Koestler writes:

our main sense organs are like narrow slits which admit only a very narrow frequency-range of electro-magnetic and sound waves. But even the amount that does get through these narrow slits is too much. Life would be impossible if we were to pay attention to the millions of stimuli bombarding our senses, what William James called ‘the blooming, buzzing multitude of sensations’. (4).

David demonstrates how our fear of madness and psychosis closes to us aspects of our experience, which we must own if we are not to imperil our world. One of my early teachers suggested that religions exist not, as we may believe, to open us up to the wonders of God and the mysteries of religion, but rather, to ensure that we are not overwhelmed by them. By complete chance – is it? really? – I have just come across a quote from Jung that “the Church serves as a fortress to protect us against God and his Spirit.” (5)

Kammerer, (quoted by Koestler), whose life was spent investigating the phenomenon of synchronicity put it very clearly:

The recurrence of identical or similar data in contiguous areas of space or time is a simple empirical fact which has to be accepted and which cannot be explained by coincidence or rather, which makes coincidence rule to such an extent that the concept of coincidence is itself negated. (6)

David Holt’s extraordinary work allows us to observe what happens when the filter is opened up a little more fully than most of us dare, so that a much wider range of data can be taken into account. The result is both a deeper and broader analysis of personal, social, political and religious experience. More than anything else, David’s work is founded in careful attention to dreams, even publishing his own, and encouraging the rest of us to do the same (7). How deeply that in itself links with my Jewish tradition and soul! How different our political and religious worlds would appear, were that to take place! What themes would then emerge into the public realm, what opportunities would develop to handle our widespread concerns and underlying anxieties? David encourages us towards a more general realisation that dreams provide a major contribution for human communication (8). Perhaps, as David would say, we would be more able to get the feeling right. In the meantime, we have The Clermont Story as a hint of what is possible and essential.

A final thoughtful and necessary response from Sacred Hunger to those terrorist attacks on New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania:

A word also about the feeling tone of what I am going to be saying. It is pessimistic……..The twentieth century has had and continues to have its catastrophes. They will continue and they will get worse.

But people will survive and some sort of world order will survive. Even though it is in a sense too late, it is nevertheless worth trying to understand what we are caught in. Because we will be able to respond to catastrophe…Our response to catastrophe can be more or less effective, more or less humane, more or less cruel. Present understanding will make a difference to future catastrophe.(p. )

Jeffrey Newman September 2001

References

1. Murray Stein, President of the International Association of Analytical Psychology (the IAAP, a Jungian grouping) writing in response to phone calls, faxes and emails from all over the world.

2. Theatre and Behaviour: Hawkwood Papers 1979-1986 ISBN 0 9512174 0 2. 1987

3. Published by Yale, 1991

4. Koestler, A. The Roots of Coincidence, London Hutchinson 1972

5. C.G.Jung CW 18 par. 1534, quoted in Giegerich,W.The Soul’s Logical Life (Frankfurt Peter Lang 1998), p.20

6. Kammerer, P. Das Gesetz der Serie (Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart-Berlin 1919) p. 93 quoted in Koestler op. cit. p. 86

7. Holt, D. Eventful Responsability (Validthod, Oxford, 1999).

Sonu Shamdasani writes, in his introduction: “In

the nineteenth century works on philosophy, physiology and psychology of dreams it was commonplace for authors to

use their own dreams as a basis for their explorations and to publish them. In this regard, Sigmund Freud’s reliance

on his own dreams in The Interpretation of Dreams followed a well-established genre. At the same time [this work

]marked the close of this genre, whose end it hastened. With the rise of the conception of dreams as disclosive of

the hidden secrets of the personality, psychologists became increasingly reluctant to publish or publicly present

their dreams, except, that is, in a disguised form. [This] is the only publication of a dream book by a

psychotherapist or psychologist that I have come across.”

8. David’s own introduction to his dreambook gives the opportunity for research into the activity of dreaming as his principal justification and adds: “one of the most urgent challenges to our imagination today is how to relate new understanding of our evolutionary inheritance with the eventfulness of everyday. If people will publish their dreams the whole climate of social imagination would change for good”.

PART I

Caught between History and Nature

Responsibility Gone Missing

I’m caught in this story which I’ve got to work out. Like a problem. A problem story.

The first Part of this book is a retrospect of the fifty two years during which the story has been with me. The second Part brings together six of the so to say professional papers in which I have reflected on the story and its possible implications. Taken together the two Parts constitute both autobiography and intellectual endeavour.

The intention is to start fresh argument between christian and non christian.

According to my story, something has gone missing between christian and non christian. There’s a responsibility which falls into a hiatus. It is about time. To take it up christian and non christian have to enquire together into their differences.

So in telling my story, I’m going to play with the words responsible, responsibility, to get them turning on (not in) time. Onto past, onto future. We say “You are responsible for it”, meaning that it is your doing, perhaps with a sense of fault, perhaps with a sense of achievement. And we say “You are responsible for it”, meaning that you have to do something about it, it is up to you to respond, to make a response, with a hint that it had better be effective or you’ll be in trouble. I want to keep reminding us of both timings.

Which is why I shall occasionally spell the word with an ‘a’, as in my subtitle. Spelt as responsibility, the word tends to emphasise the past. Spelt as responsability it emphasises more the future, an ability to respond to what’s now.

In this play on responsibility I am trying to make what I believe to be a very important point about time: that the present is when beginning and ending come together. The present is constantly a beginning as well as an ending, an ending as well as a beginning. Now is all the time we ever have. Without it, there is no future, no past. ‘Now’ is time making itself felt as responsibility.

The ‘when’ of death makes the point well, and in doing so explains my title for this first Part. Aged seventy five, I think often of when my death is to be. In my teens – I was thirteen in 1939 – we were being taught that we were already of an age to kill and to be killed. How do we correlate the ‘when’ of such different kinds of death?

We take time into our keeping. We assume, or presume, responsibility for time. And in doing so we separate history from nature.

It is this assumption or presumption of responsibility which is getting lost in the hiatus between christian and non christian. Because, and here I want to remind readers of my stammer, it feels TOO BIG.

My story is heavy with that too big. For instance, I shall be speaking of a peculiarly christian responsibility, a christian responsability for the future that requires us to take into account christian error. The feeling of what I have to say here can come across as excessive, absurdly exaggerated, better left unspoken.

Please allow for this. My argument depends on it. It is not something to be got rid of in the interests of simplicity or clarity. It is what being responsible for time feels like.

Clermont

The Clermont story originates in a dream which I had in the early spring of 1948. Clermont is a town in central France, where I had spent a week in the previous summer. The love affair which took me there had subsequently ended, and the ending precipitated my going into analysis. I was also reading history at the university at the time, and my imagination was caught by the fact that the first crusade had been preached by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095. My story originated in this coincidence of place.

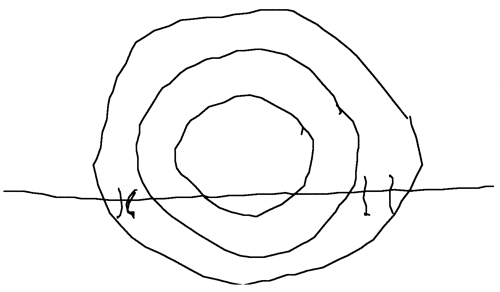

The dream came in the night of February 27, 1948, early in my psychoanalysis with Irene de Castillejo, a Jungian analyst practising in London. Thus:

A story which I am telling second hand.

I have shown to the person to whom I am telling it a plan of the story. A certain number of circles dissected by a straight line. Not certain whether the line went through middle of the circles. The line is marked with segments showing two days of the week (?Tuesday and Thursday).

The story: a girl and I have been living together in some open country, say South African veldt. We have been living together since birth or since extreme youth. My sex early on seems vague – the boy says to me cynically:

“Anyway, I’ll be seeing you more and more with less and less clothes on”.

I chide him for this.

A lot of old women in the tribe begin to get suspicious of our “goings on”. One night we ride out into the veldt, turn our horses loose to graze, and then walk into some trap set by all these women.

I am now male definitely. This trap is very sad. We were living beautifully and then all is wrecked by these spiteful hags, two of the ugliest of whom are to be sort of chief judges.

Girl and I are left alone – she now seems to be on the side of these hags.We are inside a tent. In order to lull her suspicions so as to escape, I – or another older man who may be Father – talks.

He says after something else:

“In that case, O is the most important vowel, letter”, and later says many words with O in them. Then “Move”.

At this, I catch the girl by her throat and bend her head back to the ground so that she cannot speak while I – or other man – escape.

But I, or he, only gets a short start, and when I am caught and brought back the girl is definitely hostile and I fear she may hurt me in some way.

When I told Irene the dream she responded by asking me to say some words with ‘o’ in the middle of them, and as I said them she wrote them down. At first, none came. Then, love. Another long wait, with no words coming to mind. Then, more easily, many more, of which I can now remember pool, dove, rock, blood, as well as the word from the dream, move. Irene gave me the sheet of paper on which she had written the words, and told me to go away and write a story, using them in that order, with some sense of the time which had elapsed between my saying them.

So I wrote the Clermont story. Here it is.

The scene was set in a mood of expectancy. Western Europe is resting after the years of attack and threat from the men of the north, resting and gathering its strength. Its feeling, in the union of mind and heart, is christian. The building of churches and cathedrals bears witness to a faith which had come, and conquered, from another quarter.

Outside Clermont lived a farming family, with the three sons that go with fairy stories. Their christian faith is simple, immediate, unquestioned. The gathering of the great Council of the Church is an event of excitement. With their neighbours, the whole family went to the field outside the eastern gate where the Pope was to speak.

Into the silence of an expectancy which by that time has become almost unbearable – the seconds long wait for my first word with ‘o’ – fall the words which tell of the Holy Places in the hands of non-believers, the sufferings of the christians in the east, and the call to crusade, to bear witness in arms to your love of Christ.

Your love of Christ: that word love all round the three sons as they walked home. Suddenly, the world is filled with new meaning, a meaning that calls them from the fields and animals to fight. They are carried on the word. It envelops them.

But only the two eldest can go. The third must stay at home to work the farm, to care for the parents. The pain of that staying: its bitterness – there was much of that in my story.

Now the time is later, high summer a year or two after. The boy is working in the fields. The heat is intense. He thirsts, and thirsting goes down the sloping field to a corner where there is a pool. He stoops to drink, and sees coming to meet his mouth the face and mouth of a girl.

He is as if transfixed. Love turns round inside him. Christ is forgotten. All that he had learned to feel for Christ is turned to the girl. Love is here: no need to journey to the east, to war, to prove his love. The proving is here, in his thirst and what he is to do with it in the presence of that face which will be broken and vanish if his own lips once touch and break the surface of the water to quench its raging.

The story stayed for a long time with that arrest of all movement as the boy kneels by the pool, refusing in his love to quench a thirst born of his work in the fields. Tension builds in the surrounding fields and mountains. The noonday silence continues, unnaturally, into a more terrible silence of afternoon, of evening on which the sun does not seem to set. The stillness is absolute, awful, as if nothing will ever move again.

It is broken suddenly. So suddenly that it all seems to be done in a moment, so quick it might never have happened. The beating of wings, a dove settles out of nowhere on the boy’s shoulders as he kneels. He sees it reflected in the pool, reaches up to seize it, to tear it, to try to slake his thirst in its blood. As the bird is torn, and the blood runs in the boy’s mouth, the landscape is wholly changed. The green is gone out of it. There are stones, rocks, stunted vegetation, a near desert land. But the girl is there, on the face of the earth, still in some way beyond the boy’s reach (is it she or he who is bound to a rock?), yet free to move with a volition of her own, no longer caught in reflection.

When she heard the story, Irene’s response was to lend me a typescript of an early English translation of Jung’s Eranos lecture on the Trinity. From what I have learned since about interpretation and transference in analysis, it is sobering to think how much has flowed from that ‘interpretation’.

Together, the dream and the story and the interpretation set me an agenda. First, there was childhood, the dawn of sexuality, entrapment, the father telling about words, a girl caught by her throat so that she cannot speak. Then, history. The alternative of christian crusade or the fields to be worked, merging into myth or fairy story, the timeless arrest at the pool, the coming of the dove, the killing and drinking of blood, the landscape changed and the girl in the flesh.

Perhaps it is better to think of it as two agendas: to find the meaning of sex, and to find the meaning of history. How they have come together and worked through each other is in a way the story of my life. Now that that life is drawing to a close it is time to reflect on what has been learned. It may not be the last word, but death surely has something conclusive to say about the meaning of both sex and history.

But to get the feeling right, two words have to be emphasised at the start: isolation, and inflation. The Clermont story has left me with the thought that I have seen, and am therefore in some way responsible for, an epochal development in the history of christianity which is not spoken of in the history books. I have witnessed, and in some sense taken part in, the killing of the Third Person of the christian Trinity, and the ingestion of its blood into the life of humanity.

This thought isolates, and, in Jung’s sense of the word, inflates. The isolation may not need much emphasis. The inflation does, the feel of being special, chosen. It comes close to madness. Psychic inflation of this kind feeds on isolation. It makes a virtue of it. It disables witness, converting it into something more like guilt, guilt to be treasured as much as suffered.

My life has had to deal with both the isolation and the inflation. This book is perhaps a last attempt to do so, to bear witness rather than treasure guilt. In which I need help.

Rudery and Mystery

Irene’s interpretation of my Clermont story directed me to the theology and statecraft of Ancient Egypt. In his essay on the Trinity, Jung refers to pre-christian trinitarian beliefs in Egypt, and what he wrote sent me to read more widely on the subject. What I found was explicit reference to the penis, in the myth of Isis and Osiris, and in masturbation as the act of creation.

As a result my somewhat furtive interest in the theology of the christian Trinity (I had been brought up as a self conscious Unitarian) was sexualised. At the time I was reading St Augustine as my special subject in the Modern History school at Oxford, having been excited by R G Collingwood’s discussion of the Trinity in his Essay on Metaphysics. Intellectually I was deeply intrigued, and Augustine’s interest in sexuality added its spice. But the explicitness of the penis in Egyptian theology made it possible for me to imagine connections between my theological reading and sexuality (masturbation, most immediately) of a kind that combined mystery with rudery.

This connection has been with me ever since, and shows no signs of losing its energy as I grow towards death. On the contrary.

Its immediate effect on the Clermont story was to get me wondering about the dove. I was familiar with the dove as image of the Holy Ghost, the Third Person of the Trinity. I read Charles Williams’ book The Descent of the Dove. But though it never seemed to be mentioned in the literature, I was constantly making rude connections between the dove and the Holy Ghost by whose power Mary had become pregnant with Jesus. Were they one and the same? If so, how could one imagine that identity? If not, then how to imagine their difference, and why wasn’t more made of that difference in the teachings of the church? And, insistently, what does this all have to do with the penis?

Thoughts like these went off in many directions. My published dreams give some idea of where. Here I pick out just one of the themes that caught my attention: the role of the penis between before and after.

The Holy Ghost that comes down on Mary so that she becomes pregnant is before Jesus is born. The Holy Ghost that comes down at Pentecost is after Jesus has died. It has something to do with his being Risen. As Jesus has said while alive, first he has to die and return to the Father. Only then can the Holy Ghost come as comforter to the world.

What happens to our understanding of the Holy Ghost if we are so rude as to relate penis to trinitarian theology?

It is the question that started me wondering about what has perhaps been the chief preoccupation of my life, the connection between sex and time. Father, son, and penis. Does sexuality simply pass through time from the father’s “before” to the son’s “after”? Or does sexuality remind us, rudely, that we have a job to do in keeping time?

Freud got us thinking about it in terms of the son killing the father. Christian theology talks of the father so loving the world that he wills the death of his son. Suppose both are wrong. Suppose that what really happens is that the penis reminds both father and son that time is given into their keeping, that between them they are responsible for keeping the present present.

Formulations like that have come much later. But they started with the dove at Clermont. The Third Person of the Trinity as a dove. How is power of the kind associated with the Holy Ghost represented by a dove? There are many answers in the history of iconography. But when imagination floods with the killing and tearing and bleeding and drinking, and then with the compulsions of masturbation, the dove opens its wings into darkness and power of a ruder kind.

Flailing and Flaying

The Clermont story contrasts the fighting appeal of crusade with the need to work the farm. For the stay at home there is no glory, no danger, no bloodshed. Not until the dove is killed.

Dreams that followed on the writing of Clermont began to change that simple contrast. Dreams associated in various ways with corn.

From the beginning, “to work the farm” meant labour, the labour of putting one’s self into the land, the body tired, exhausted, hurting. Then there were dreams of corn, and with them the thought that agriculture could be in its place as violent as any crusade. Seed that had to die so that corn can come. The contrast between the scattering of seed and the gathering of corn, and the necessary time between.

But perhaps the crucial idea in opening up the essential violence of agriculture was of how the corn is treated so that it may become food.

This came through another dream, six months after Clermont was written. (The full text can be found in my dream book, October 8, 1948.) This was of a working man, a railway porter, who gets caught up in a machine that he is supposed to be using. As a result his body is “flailed”, like corn is flailed so as to separate the grain from husk and straw. In the dream there is confusion between the verb to flail and the verb to flay. Is his body perhaps also being flayed? Later in the dream “I find myself thinking of the Crucifixion of Christ. I begin to understand – what was important was the complete fear of NOTHINGNESS, of non being, of utter non existence, a gaping VOID – Christ had faced that fear in utter solitariness and come through”.

Working with that dream I found that the turning of corn into food became associated with acts of unexpected, appalling, pornographic, violence inflicted on the human body, a body flailed to pulp, a body flayed alive.

It was only gradually that I realised what was happening. In my imagining of the christian story another picture was appearing alongside, or perhaps instead of, the dying body nailed to a cross: a body kept wildly in movement, a body skinned, a flailing that was also a flaying, a flaying that was also a flailing.

Within the Clermont story I began to feel connections between the tiredness, exhaustion, hurt of the boy working the farm, and the tearing of that flesh carried on the beating of wings. And so another story came.

Christ is walking alone in a land which is between desert and cultivation. It is farm land, working land, in danger of wilderness but responsive to man’s labour, land in which people can settle and make a living so long as they do not take it for granted. As he looks round him, he sees fields and animals and plants which bear witness to human labour, and also hills, rocks, birds, clouds, which owe nothing except their being seen to man.

He is praying to the father. In prayer, the will of the father is being made known, the will that intends Calvary. As he prays, tension is generated within the landscape round him, tension similar to that by the pool at Clermont.

How to describe that tension? The air was full of it. An at-tension held between water and clouds, stones and earth, and moving from them to inform plants and animals. How do clouds and rivers, stones, plants, animals, attend to each other in the presence of a humanity which they must suffer but cannot comprehend?

Out of that at-tension a cry goes forth. It is like a whisper, a murmuring, all but inaudible. And yet it pierces the ears. Like one of those whistles which dogs can hear, but humans not. A mute, inanimate cry from the fields and the rocks and the hills, from the movement of the waters and from the stillness of the sky: “For the love of God, don’t do this thing to us”. A cry from inanimate creation to the son of man not to go up to Jerusalem, not to set in train the sequence of events which would lead to crucifixion, resurrection, Pentecost.

I was beginning to realise that there is a difference between nature and history which is in some way my responsibility.

Tudor sexuality

The immediate reasons that took me to baptism and confirmation in my early thirties had to do with marriage and the birth of my first two children. But it was history that prepared the ground and made those reasons compelling.

Certain parallels, or suggestions of common themes, between the origin of the Anglican church in Tudor England and the early days of christianity had occurred to me while reading history at Oxford during those first months as the Clermont story began to do its work. A virgin played an important part in both. There were connections between sexuality, killing and the begetting of a son. The names Elizabeth and Mary recurred, though their roles were different. There were two Marys, one virgin and barren, the other mother of kings. But the mother had her head severed from her body by orders of the barren virgin.

For the professional historian such parallels carry no weight. They are fancies. For someone beginning to sense a connection between sexuality and time, they were rudely, vulgarly, even obscenely, teasing. They made the origins of the Anglican church much, very much, more interesting. The burning of heretics and the politics of inheritance could be read about while anticipating masturbation. A church that knew about the pornographic violence perpetrated by catholic on protestant, by protestant on catholic, made possible, invited even, obscene thoughts about that original foundation fifteen hundred years earlier.

In being both catholic and protestant the Anglican church turned between past and future. So if as the established church it claimed respectability (a respectability that had once excluded my grandfather from the pulpit of Liverpool cathedral) it was also shocking, historically shocking. The sense of history as shocking was growing, and once again, entwined with family. Baptism and confirmation were a response to that entwining, a stepping into history to acknowledge the presence of sexuality and killing in the passing on of political authority, social cohesion, and religious faith.

Personality

When I was thirty two, in 1958, my wife suffered a massive stroke while we were on holiday in Italy. The initial prognosis was that she would not speak again, and would not be able to walk. The outcome was very much better. Within weeks she was talking, oddly but engagingly, and walking with a bad limp, not unlike the roll of a sailor. Eight years later we divorced.

Susan’s stroke is from many points of view the defining moment of my life. It flows into everything that has happened and been done by me since. Its effect on the working out of the Clermont story was momentous. It broke my understanding of personality.

After some months of dramatic and, given the initial prognosis, almost miraculous recovery, the process of rehabilitation and adjustment became steadier. It was some time during those months that I said to myself, in a moment of angry despair, “I shall never believe in personality again”. What I was trying to recognise and establish in myself and vis a vis the world was a sense that in order to live with what had happened, to adapt, I had to stop pretending that there was something called personality that could be relied upon.

This conviction, born of an at times murderous rage, got me interested in the brain, its part in the operation of body and mind, its evolution. Also, perhaps it was here that my interest in theatre began to take hold. And in relation to the Clermont story it made possible an altogether new kind of interest in the Trinity.

Theology speaks of the three Persons of the Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. I had learned that the word Person was from the Latin translation of the Greek υποστασισ, which meant something very different to our understanding of person. And I had learned that the translation between the two languages had led to centuries of misunderstanding, debate, and differing illumination. But how did all this relate to the identity of the dove at Clermont? Did my “I shall never believe in personality again” help in understanding the role of the Third Person of the Trinity?

My response to Susan’s stroke left me with an obstinate conviction that personality was something essentially experimental. Obstinate because it belonged with survival, my own survival, Susan’s survival, the survival of those who depended on us. In order to survive I had to learn to make do with personality as something essentially experimental. My understanding of the Clermont dove began to be affected by that making do with the essentially experimental, a making do that could sometimes feel like murderous rage.

Zurich and the Theatricality of Being

Such was the state of the Clermont story in April 1962, when I was confirmed into the Anglican Church by the Bishop of London in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral. A month later I began my four years of study at the C G Jung Institute in Zurich.

During those years I found myself in a community sympathetic to Clermont, in that Jung’s engagement with christianity, particularly in his alchemical works, seemed to be within the same matrix of faith and doubt. It was after all his Essay on the Trinity which had been offered me as interpretation of the story back in 1948.

But I also found myself learning a lot more about the psychotic and hysteric modalities of my own being.

By psychotic I mean a shattering and shivering of the mind which is also an emptying out, an evacuation. Psychosis allows something alien to take over the mind. It shows on the face as a fixedness giving way to something secret. Faced by the incomprehensible the mind allows the alien to enter in. It is crazed. It is also, to use a term from the second world war made familiar to me in my dreams, its own fifth column.

By hysteric I mean the use of pretence in dealing with the unmanageable. Hysteria is responsible in the literal sense of being a response to something out there. It is irresponsible in using make believe as a way of avoiding what we can’t manage. It is clever, but clever in a way that may well not be right.

Played across each other, the psychotic and the hysteric can generate their own way of being. In Zurich I began to realise how attractive this way of being could be for me. One of my two analysts interpreted Clermont as evidence of this, and nothing more. I was not convinced.

But there was more to come. In 1964 and 1965 I began to put my experience of personality as essentially experimental in what I now believe to be its proper context: the theatricality of the world. Or, perhaps better, the theatricality of being.

The thesis with which I graduated in February 1966 was titled “Persona and Actor”. My Introduction read as follows.

One of my first control analysands was a young woman whose initial dream featured an actress preparing to play the part of Ophelia. This acting theme recurred in her dreams. Sometimes she was playing the wrong role: sometimes there was no audience, or she was playing before the wrong audience. In the thirty first analytical hour she produced a dream in which she was sitting talking with a man about the ‘hypokrites’. She explained that by this she means the Greek word, which she remembered learning at school meant actor and did not then have its modern meaning of ‘scheinheilig’. She was sufficiently impressed by the dream to look up the etymology of the word, which was further discussed in the next hour.

This word hypokrites focussed my attention on the extent to which ‘play acting’ characterised the analysand’s attitude to the therapeutic situation, and also to her life as a whole. Once I had recognised this factor in the analysis, I came quickly to feel that I could not understand what was going on unless I learned more of the wider significance of acting in the traditional theatre. The analysand shortly afterwards saw the film version of Genet’s ‘Le Balcon’. She was impressed by it, and promised to write me a critique of the film. This she did, but destroyed it before showing it to me.

This event determined me to read more widely round what might be called the ‘philosophy of the theatre’. I turned to Jung’s works to read all he had to say on the persona, but found little that seemed to apply to my analysand. It seemed to me then that Jung’s descriptions of the persona were concerned with social and professional ‘roles’, but not directly with what an actor did and was, nor with the more mysterious link between actor and audience on one side, and actor and the plot of the play on the other. In thinking about my analysand it seemed to me that this three cornered relationship, actor, plot or action, and audience, was the necessary frame of reference within which to understand what was going on in the analysis. In our case we had the actor in the person of the analysand, and the audience in the analyst. But that which should give meaning to our coming together, the plot, was undefined; not merely undefined, but concealed with a sort of natural and instinctive skill which I came to believe had something to do with the inherent nature of the actor.

It was at this time, in the summer of 1964, that the Zürich Schauspielhaus produced the two Parts of Shakespeare’s Henry IV. These two plays culminate in the famous Rejection Scene, in which the newly crowned young King banishes Falstaff, the boon companion of his youth. There is something in this dramatic situation which reminds us irresistibly of Jung’s definitions of the persona, in terms of social and professional roles. The young King has quite literally assumed a new role and the dramatic effect of the scene depends on the consequences which that role brings with it.

I decided therefore to make a study in depth of this particular dramatic situation, to see what it might have to teach me about the nature of acting. I believe that this scene has proved a happy choice, because in it we have ‘acting’ on two levels. There is the theatrical level, on which the young King is confronted with one of the most ambiguous and many layered characters of European drama, Falstaff; and there is the level within the play, in which a prince assumes the persona of king, a level to which Jung’s various definitions of persona apply. It has therefore given me an opportunity to consider the persona against a very rich theatrical background, a background that has convinced me that ‘acting’ means much more than the limited significance that Jung attributed to the persona.

The shape of the thesis derives from its origin. The first Part is a detailed study of the dramatic movement that culminates in the Rejection Scene. My aim in this first Part is to define the two chief protagonists in that scene, King and Falstaff, by answering the questions: what is being en-acted? For whom is it being en-acted? What is the nature of the relation that links actor, audience and action? In the second Part I draw conclusions as to the nature of acting from the analysis in depth of the dramatic situation made in the first Part, and relate those conclusions to what Jung has to say about the persona.

Personality as something I could no longer believe in was making room for personality as experimental. And together with this, both demanding and sustaining the experiment, realisation of the world as en-actment.

This was the beginning of an interest in theatre which has been central to my clinical practice for thirty years and more, an interest which has I believe helped me in responding to the psychotic and hysteric modalities of my own being.

The Clermont story got taken up into this new interest in the theatricality of being. Drama, δρωμενον, the thing done: the world as story to be enacted. Clermont assumed christian responsibility for that enactment but continued the story beyond that told in church.

I look now at the six papers, covering the years from 1974 to 1994, which are reprinted here as Part II. What do they have to say about the continuation of the Clermont story?

First Paper – the Yes and the No of the Two Virgins

1974: Jung and Marx: alchemy, christianity, and the work against nature.

Is capitalism the result of the killing of the Clermont dove and the drinking of its blood? Or, with less inflationary grandiosity, is the Clermont story one young man’s attempt to come to terms with his capitalist family of origin?

I had been introduced to Marxist understanding of the meaning of history in the navy in 1944, when living in cramped quarters with men for whom the name Holt was synonymous with capital. Reading history at Oxford after the war I had as one of my tutors Christopher Hill, with whom we argued about Marxist interpretations of the 17th century and the English civil war. Christopher and I both stammered, though his was more on the in breath than mine, or so I remember it. I could feel very close to him. Marxism at Balliol helped me with the marxism I had been exposed to in the bowels of an escort carrier. But the naval experience had given me what I can call a family interest in marxism which developed across the argument with Christopher.

This family interest was picked up in my Jungian analysis, in particular by the historical chapters in Jung’s book on Psychological Types. Jung’s distinction between extraversion and introversion, and his reading of that distinction in philosophy, theology, aesthetics, became a two way channel between family stuff, in particular the turbulence of sexuality, and the search for meaning in history. In this paper, first read in 1974, I tried to say something in public about this two way channelling.

But in preparing the paper something occurred which was to open the Clermont story into sexuality in a new way. It was about a week before I was due to speak, and I was stuck as to how to bring the paper to the conclusion it was reaching for. My wife and I were at a concert. I was thinking about the work against nature rather than listening to the music. And suddenly I knew that I had to speak of two virgins, and of the contrast between them.

What I’d got stuck in was the ‘space between creator and virgin’. My paper was using the idea of such a space as a way into the work against nature, to stimulate both extraverted, marxist, and introverted, jungian, movements of the imagination. I was trying to create a sense of nature becoming aware of what it means to be used for a purpose outside itself. To do so, I was comparing the history of economics with theologies of creation, and coming close to possibly psychotic confusions of sexuality and hunger.

It was somewhere there that I got stuck. What then came was a sense of choice. There was a choice that could be made, a choice inherent in what I had been calling the space between creator and virgin. The virgin could say yes or say no. The virgin could be inquisitive as to what the creator was up to, and this inquisitiveness might compel creation to change direction.

The virgin as inquisitive. Though I did not realise it at the time, this new sense of the virgin as inquisitive changed what I think of as the purchase of the Clermont story on my life. The hold that the Clermont story has over me was reformulated. The change of state between the girl in the pool and the girl on the face of the earth was reminding me of another time, a time when the virgin could have chosen to say no, so that Gabriel would have had to contain his message, or, like Onan before him, spill his seed on the ground.

Ideas such as these do not have a place in our history books. They are both mystical and vulgar. Yet if we are indeed caught in a work against nature they may be responsible in ways we don’t yet understand. They allow thirst and hunger and sexuality to play across each other as we try to find our place in creation. As I put it in the 1974 paper, they can help us realise how christianity has damaged matter, and how the human psyche moves spontaneously to make good that damage.

Second Paper – Sado-masochism and the Peculiar Numinosity of Machines

1976 – untitled

This paper has not been published before. I came across it while clearing out old files, in the summer of 2000, when the self styled “fuel protests” were all but bringing the country to a stand still. Its argument seemed immediately relevant to the schizophrenic mood of the time.

It appears to be written for a talk I was to give at one of our Jung weekends at Hawkwood College, in 1976. It seems to be unfinished, and I have no recollection of what happened to it. But perhaps it was as a result of that weekend, probably with Molly Tuby and Niel Micklem, and perhaps others, that we began to prepare ourselves for that unforgettable occasion in 1980 when we enacted the illustrations from Michael Maier’s alchemical text “Atalanta Fugiens”.

I find it interesting as a reminder of how my thinking was developing around the age of fifty. It develops the argument of the Jung Marx paper with reference to Lévi Strauss’s La Pensée Sauvage, and Peter Berger’s three books The Social Construction of Reality, The Social Reality of Religion, and The Rediscovery of the Supernatural. And it does so by including verbatim transcripts of six of my dreams from 1956, 1957, 1961 and 1962.

But with the self strangulation of those fuel protests in mind, it is the sado-masochistic theme which causes me to publish it now. The term is Berger’s, “emphatically not to be understood in Freudian or other psychoanalytic terms”. His use derives directly from Sartre and through Sartre (though he does not make this explicit) from writers such as Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Marx and Hegel, and he relates it in particular to what he calls “the interpretations of last resort”.

By which he means the problem of how to justify the ways of God to man (which can include the denial of God’s existence), and he emphasises that in this underlying and all embracing problem of theodicy (which surely is what Clermont is about) the sado-masochistic attitude “is one of the persistent factors of irrationality, no matter what degree of rationality may be attained in various efforts to solve the problem theoretically”.

In my paper, I relate it to my dreams, and through them to traffic jams, the breakdown of the marriage between Christ and His Church, the nerve centre of a sex organ that is neither, or both, male nor/and female, the christian devil, the turn between the outside and inside of our hands, and the peculiar numinosity of machines.

Third Paper – Repetition of Repeated Reversal

Jung and the Third Person, 1981.

This paper was an opportunity to get my confused ideas about the Trinity into some kind of order. In doing so I had to think a lot about time. The result was to prepare me to talk more confidently, more publicly, about the Clermont story.

In reading what I say in it about extraversion and introversion (once again, essential in my attempts to apply Jung’s psychology to the world I find myself engaged in) it is important to dwell on that startling conjunction of mystical theology of creation with the bitter sense of dishonouring.

The two women involved on that occasion were both within what I thought of as my working family. My sense of being caught within, and in some way responsible for, the scene where such dishonouring could take place, was insistent. It is still with me. And it was this intimately familial and personal discomfort, or even shame, that illuminated, and was in its turn illuminated by, a moment in the history of Jewish mystical theology.

To understand how this affected my thinking about time it is necessary to refer to a dream of mine. It is the dream which got me thinking about extraversion and introversion in relation to creation, to the question: how is it that the world is as it is?

April 10, 1954

Within the dream, a dream within the dream. And this inner dream is a long murder story whose function is to persuade the dreamer that he is a murderer in imminent risk of being discovered.

I’d had this dream untold times before. It is indeed at the root of my worry and fear of life. But this time I ‘alter’ it to show that its grip on me is gone. It is as if at the crucial moment which contains the whole point of this story, my mind turns and says ‘No, this is not real for me’, and a clenched hand is unclenched.

As a result of this unclenching I see a great design, a world picture. It is made up of an intricate arrangement of an endlessly repeated theme. This theme is of a tree growing in a formal courtyard at the top of a flight of steps. These steps lead down to a square pool of water. Although the water is still, there is immense energy generated within the pool. Between the tree and the pool there flows a narrow red stream, though it is not clear in which direction, and this stream is the life of man. This theme of the tree and the pool is repeated an infinite number of times. It is as if everyone who had ever lived spent his life painting one such tree/pool picture. All the separate pictures are arranged together to form part of a great tree, but I see that in one of them ‘the direction is reversed’. This means that in one of them the direction of flow of this red stream between the tree and pool is reversed, and this reversal of direction ‘spoils’ the whole picture, and seeing it I feel an indescribable horror; it has something to do with a reversal of direction in masturbation, which is connected with the locking of my stutter.

In thinking about the Clermont story that vision of reversal of direction, and the indescribable horror that went with it, has been a constant since 1954. The association with masturbation and with stutter continues to affect me. If I have managed to humanise some of the psychotic and hysteric potential in the Clermont story it is largely due to that dream. Because it started that parting of the mind that can allow for creation, a parting that works with both the psychotic and the hysteric.

In Jung and the Third Person I talk about that from various points of view. In relation to the Clermont story it is the argument about time that matters.

Clermont left me with questions about the role of the penis between before and after. What is common to father and son questions time. Between the generations there is an Other, common to both yet timed differently, timed in a way that somehow synchronises before and after. This Other questions our understanding of time. It takes the words ‘from’ and ‘to’ in the sentence “from generation to generation”, and turns them into a momentous and in ways unbearable question.

This “questioning time” had seemed so peculiar, so unrecognisable, to the people with whom I had tried to talk about it, that I had done little with it. Working on Jung and the Third Person changed that. It confirmed me in my belief that there is indeed a question about time pulsing all round us in our world today, and that one representation of that question is the penis.

Which explains perhaps why it eludes public discussion. If it is to get a hearing we are going to have to listen to unexpected, perhaps even psychotic, resonances. In reading the paper listen for that word dishonour when there is talk of time as ‘something discontinuous, a repetition of repeated reversal’, alert for feelings of intimate, personal, familial obligation that are in some strange way dishonouring. In my discussion of the Cronus myth, remember masturbation. Is the compulsion to masturbate evidence of an obligation to be doing something about the beginning and ending of time? Something both gruesome and divine. In my references to evolutionary theory there is talk of sex and death as invented. Evolutionary argument should be pulsing with questions about our responsability for that invention now. But to hear them, to feel them “arise”, we are going to have to share our vulgarity more openly. The invention of sex and death is not nice. It’s rude. Like masturbation.

Fourth Paper – Apocalypse and the invention of the method of invention

1983: Riddley Walker and Greenham Common: further thoughts on alchemy, christianity, and the work against nature.

This was my first public telling of the Clermont story. I was 57.

It is a response to Russell Hoban’s wonderful book Riddley Walker, and should be read with that book in mind.

I had sent Hoban a copy of my Jung Marx paper, to help explain my enthusiasm for his book. I still have his letter in reply.

27 May, 1982

Since talking to you on the telephone the other day I’ve read your letter over two or three times and I think that your perception of a violence done by us within metaphysical reality is utterly correct. As I write this it occurs to me that we cannot properly speak of a “metaphysical reality” as separate from the reality that we walk about in every day; there’s only one reality; one might perhaps refer to a range of perception relative to it as one refers to frequency coverage in a shortwave radio. It seems to me that this act of violence that you speak of has been a kind of anti-cathexis by which humanity has withdrawn from its original being. All of us, being particles of one universal mind, are affected by it and know about it at some psychical level but not all of us are aware that we know about it. I think that a great many of our actions have to do with compensating for or trying to regain that lost connexion.

I’ve been thinking about what I might send you of my unpublished writing, and for the moment I’ve decided on the enclosed essay. I wrote it in 1980 but I haven’t altogether come to grips with the material of it yet – it’s something that I refer to often. My inability to be with the black-and-white bull of Evangelistrias correctly and the idea of storing for retrieval a world that we don’t know how to live in are part of the violence that you have been addressing yourself to.

On page 4 of your paper you say: “A thousand years of intricate and passionate reflection on the mysteries of the christian faith and practice have separated mind from its original participation in nature. Within the space made by the separation man had room to experiment, and to sustain his experimenting, in a way that had never before been possible. He learned to enjoy putting nature to the torture.”

I think that the cult arising from the torturing to death of that particular man on that particular tree marked a turning in the path of human mind that remains a psychically magnetic point of reference with which not much can be done at the rational level. I’ve avoided reading Jung; I bought his Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious about twelve years ago but I found that I didn’t want to know what he had to say, and I’ve never read the book; I prefer these things to come to me how they will within the limits of my perception.

Apropos of your “cry from inanimate creation to the son of man” here is a bit of Pilgermann, the new novel I was copy-editing when your letter arrived at Cape:

“The humps and hollows of the landscape tend always towards the human: on this day the horizontal head of Christ was clearly visible in woods and fields and rocky outcrops. It was the head of the dead Christ brought down from the cross, his eyes closed, his passion complete. I sensed that it was important not to tilt my head to the horizontal the better to see his face; while I had no wish to make with the vertical of my head and the horizontal of his a cross, neither could I in good conscience avoid it.”

Thinking about Christianity (I note that you rate it a lower case) now as I write this letter I find in my mind the idea of a pulling up, a violent pulling up – I think of a mandrake root being pulled screaming out of the earth and nailed to a cross. You associate your idea of a metaphysical violence with Christianity, and the idea of a violent separation of the human from the rest of nature is clearly in it.

When I gave my paper to the Jung Club, Hoban was present. It was because of his story that I was telling my story, and Clermont has not been the same since.

This was my first attempt to spell out my growing belief that christianity is responsible for the technological conquest, or is it conversion, of the world. My argument, as my title, followed on from the Jung Marx paper, but with much more added.

What I think of as the historical sections must speak for themselves. But I want to comment on what this public telling did for the isolation and inflation invested in the Clermont story. Was it just a private heresy, or did others recognise it as speaking of a world they knew?

Two letters I received after it was published define the range of response which I got. One was enthusiastic, the other like a douche of cold water.

First, the enthusiasm. This was dated 30 March, 1984, and was written from the Hotel Garni at the Methodist Centre in Zurich, first on a sheet of hotel paper, then on two scraps added. It was from Joseph Wheelwright, an American of the generation that had analysed personally with Jung. I had met him at two of the International Congresses of Jungian Analysts, but did not know him well.

Dear David, I have just finished reading your piece in the recent copy of Harvest [that was number 29, 1983, in which my Riddley Walker paper first appeared, followed immediately by a paper by Wheelwright on Intimacy], and I have been very moved by it. Nothing less would have impelled me to write. I am internationally known as a man whose writer’s cramp a galaxy of analysts couldn’t cure. Not that I helped them much.

I felt a deep kinship to you, though we have travelled very different roads. But it seemed to me that for us both the bottom line was a passion for humanity and an unshakable belief in it. Most certainly I concur in the necessity to share our deepest feelings, and to hell with the embarrassment and the snide remarks about unbridled narcissism. And we are both story tellers. I am glad that we are published side by side. And I learned a lot about the eucharist, and Christianity from you. I have never thought of myself as Christian – nor God forbid (sic!) as anti-Christian. Relationship and intimacy have been my life, not scholarship and informed – even illuminated, at time – thinking such as you deliver. But I feel we’re headed in the same direction. But we do have it in us to accept our responsibility to humanity. I’m inclined to think it will be women who will save our bacon. Yours Jo W

[Now continued on the scraps]

Short addendum: There was a man named Maurice Nichol (s)?, who was extremely influenced by Jung before World War I. (Jung and Mrs J were god-parents to their first born.) In any case, he wrote a play called ‘Wings over Europe’ about 1926 or 7, which I acted in. It was about a young physicist who presented himself to the British Cabinet and said: “I can split the atom. Here are all my figures – I give them to you for this discovery belongs to humanity”. The whole action of the play is a discussion by the cabinet. They call – [Damn, I’m out of paper] – him back and the P.M. says: We very much appreciate your giving us your findings and applaud your unquestioning belief that they will be used constructively. Unfortunately we remember that though the Chinese discovered gunpowder and used it for firecrackers, it didn’t take Marco Polo long to see that it could be a notable instrument of destruction. Our consensus was that your work is too dangerous and we have destroyed it. End of play. This came to mind from a remark you made at the start of your paper.”

Then, the cold douche.

This was from R W Southern, the mediaevalist whom I had quoted in trying to evoke the thinking about the eucharist which was developing in Western Europe at the time of the first Crusade, the time when my story was set, a period characterised by what Southern described as ‘profound modification of thought’. Dick Southern had been my tutor at Balliol after the war. He had introduced me to the work of the philosopher R G Collingwood, who got me reading St Augustine, who sent me to read Jung: a truly formative influence, a person to whom I knew and know myself to be deeply and gladly indebted. So I sent him a copy of the printed paper, saying that it was perhaps rather crazy, but…. I forget my exact words.

His reply was characteristically generous, but it confirmed me in my sense of isolation.

Dear David, It was an unexpected pleasure to hear from you again after all these years. I had caught faint glimpses or reports of you for a few years after you went down; and then a cloudy vagueness descended, which has now been pierced, at least in one area, and I was glad to hear something, to read words which say something about your plans for the future.

I confess to being rather bewildered by what I read: ‘crazy’ it was not; but certainly bewildering – chiefly, I suppose, because you start with a foundation of experiences, which (so far as I can see) – vivid though they are – tell us nothing about the past experiences of the human race – or at least nothing on which we can build.

My idea of evidence must, I think, be quite different from yours. Of course I can’t say that yours is wrong, and mine right; but it makes it difficult to find a common ground and I don’t think I know any books which have the same foundation as yours.

Of course you will know Keith Thomas’s Religion and the Decline of Magic (I’m not sure that I’ve got the title quite right) and perhaps Alexander Murray’s Reason and Society in the Middle Ages. But, though they discuss some of the same subjects as you, they discuss them from a much more orthodox historical view point that you do. The same would be true of Colin Morris’s book on the Rise of the Individual in the 12th Century. What they all have in common with you is that they are talking about powers in the soul (or mind or spirit) which have not in the past been thought of as the proper subject of History. But though they stretch out beyond the conventional ambit of history, they do so with traditional ideas of what historical evidence is and how it should be treated. And this (if I understand you) is what you don’t do.

The result of this was that, though I was arrested by something in what you wrote about the experiences out of which your historical structures had grown, I could not really find much substance in the structures which you proposed.

I fear this is the response you must only too often have heard from your more conventionally historical friends, and I wish I could give you a more positive response. But at least I’ve had the pleasure of hearing something of what you have been doing; and I can send you our very warm regards and good wishes for what you are doing now and hoping to do in the future.

Though Dick’s letter confirmed me in my isolation, I think, looking back, that its warmth and generosity gave a new friendliness, almost a sort of conviviality, to my alienation. In particular, “which……vivid though they be – tell us nothing about the past experiences of the human race – or at least nothing on which we can build“. Those last words somehow gave me hope. Dick had written ‘work’, then crossed it out and substituted ‘build’. Isolated, even autistic, I might be, but perhaps not so inflated. There was need for work. With which I could agree.

I had many other responses to Riddley Walker and Greenham Common. But those two letters define well a field of judgment and emotion in which they can all find a place. Friendship always. But friendship voiced between puzzlement that verged on dismissal, and intimate recognition pointed with the history of the Jung movement and of this century of atomic energy that has been ours to make and endure, enjoy and survive.

But there was something else which this telling of the Clermont story in response to Russell Hoban’s story did for me. It confirmed me in my belief that we are going to have to learn how to take responsibility for ‘the invention of the method of invention’, and that that learning will involve, is already demanding, a deconstruction of christian theology that goes far beyond the Protestant calling into which I was born.

Fifth Paper – A Special Kind of Curiosity

1988: Alchemy and Psychosis: curiosity and the metaphysics of time.

In this paper personal exposure is brought together with my interest in the history of science and technology. Reading it through today, twelve years after it was composed, I wonder whether the personal material and the interest in history can illuminate each other without further cross references.

The personal exposure is most evident in the two dreams, one from 1955, one from 1962. These can now be read in context with other dreams of their time in my Eventful Responsability: fifty years of dreaming remembered, copies of which are in many Jungian libraries. To connect these with the history of science and technology we need curiosity of a special kind, the curiosity which has drawn many of us to Jung’s work on the psychology of alchemy: curiosity about sexuality as our way into what the animal, vegetable and mineral worlds have in common.

We can start with the theme of the two virgins, the jewish girl Mary and the alchemical Isis. I write of nature as virgin, and nature as used for a purpose outside itself, and my feeling that between the two there is need for some kind of sacrifice. I speak of curiosity about sex, about money, about worship, all feeding into this nucleus of feeling.

Which takes me to the Two Bodies, the personal body and the social body. I talk about the tension between them that allows for the elaboration of meanings. If we are to make sense of the sexual contradiction, which is also a metaphysical contradiction, between the Yes and the No of the christian and alchemical virgin we have to be curious about that tension. To do so, our feeling has to acknowledge and allow for shiver of a special kind, shiver that is both psychotic and worldly, personal and social. We have to imagine a fracturing of the air we breathe, a distortion of the light by which we see, a rupture in the rhythm of our breathing, a breaking of the word which makes human communication possible.

Are the christian mysteries asking to be retold with such a shiver in mind? In the tension between the Two Bodies today what happens to the worshipping mind as it dwells on Annunciation, Virgin Birth, Crucifixion?

I go on to talk about the relationship between ecology and sexual behaviour, between our understanding of and respect for the balance and consistency of our environment and the whole nexus of transaction between male and female. There are connections between the sexuality of our bodies and social responsibility for our environment that are crying out to be spoken of. For instance, marriage, one of the most familiar examples of the tension between the Two Bodies. Is there evidence of an investment in hurt which is all but unimaginable? The world of alchemy of which Jung reminds us is full of suggestion as to how human sexuality and the work against nature go together. Is marriage being asked to carry the hurt of that “work against”?

So I move on to curiosity and respect for Being. I am talking about a new kind of attention. Or rather, an old, a very old, kind of attention that has to be renewed if it is to play its part in our scientific and technological world.